SOURCE: ENS

On a full-moon night, atop a hill in Manipur, Yumnam Rajeshwor Singh reads the names of the dead. They may have been gone from this earth for 76 years, but time is relative for Rajeshwor, a man with a plan — and dozens of maps.

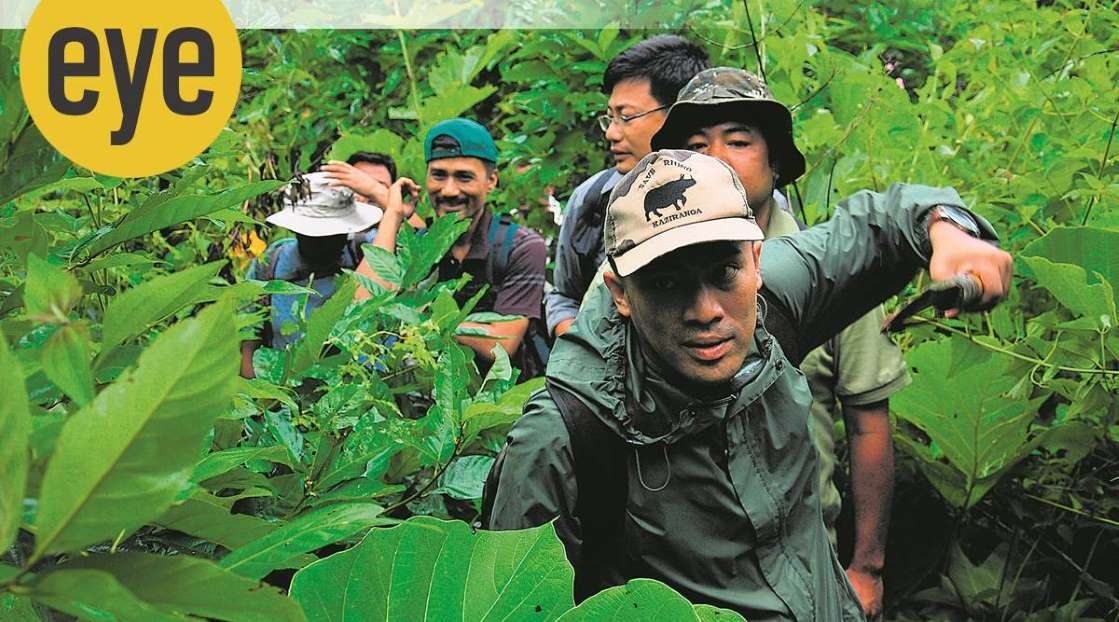

“We are on this ridge,” he says, tracing a finger along a route on an A-4 size copy of a map from 1944. “And there — there were the Japanese bunkers! From where they fired.” He points a little further away, in the direction we had trekked from — carrying everything from pressure cookers to metal detectors, tents and canned fish — earlier that morning. Of the 10 who had embarked on this journey, only nine made it, after one took ill en-route. The nondescript hill, about 15 km from Imphal, isn’t for the faint-hearted. It was after all, one of the many battlefields of the Siege of Imphal, where the Allied and the Axis powers fought between March and July, 1944, in some of the fiercest battles of World War II.

Rajeshwor gets back to reading his list of the dead soldiers — aided by the flashlights of three phones — before he stops at one. “Private Tod D,” he says, “This is the guy we are looking for.”

In early March, when Rajeshwor drives me to the hill to look for the remains of David Tod, a British soldier who had died in the war, the skies are blue and the days are glorious. The newspapers have some news about the virus from China entering India but few in Manipur think of it as a threat to them. If China is far away, Delhi and Mumbai are probably even farther. Rajeshwor, who works in a telecommunications company in Imphal, has his itinerary chalked out. “I will be on my tour from March 28 — UK, France, Belgium,” says 43-year-old.

For months, I have been persuading Rajeshwor to let me join his World War II excavation expeditions — where he and his friends travel the hilly Manipuri countryside, unearthing relics and remains, stories and memories from the twin World War II Battles of Imphal (Manipur) and Kohima (Nagaland).

Initially, he tells me that these are “secret” things that happen in the “complete absence of media.” But earlier this year, when I send him my customary monthly WhatsApp message asking him if he has changed his mind, he finally relents, but with a caveat: “Please don’t mention the exact location in your news.”

He did not need to worry — with my despicable sense of direction coupled with the wilderness of the hills, I have no idea where we are. “People talk about things they see and read in books, but neither of these battles have been included in school curricula,” says Rajeshwor, at the wheel of his “rickety but reliable” Chevrolet UVA, which takes us to the base of the hill we are meant to climb.

Ten minutes into the climb, I understand why Rajeshwor had told me: “I hope you are healthy.” The hill is far from kind: my running shoes are not equipped for the terrain, and I slip, stumble, fall, and on certain portions, comically crawl up the hill. To think of men vying for each others’ blood, with guns and bayonets in hand, seems a ridiculous idea. But I am less amused when I see the 72-year-old member of the group, trotting up the hill, way ahead of me, with the support of one thin stick.

Rajeshwor hangs back to tell me his story. Like many others, he grew up in ignorance about the WWII battlegrounds. More than seven decades ago, this hill was one of the many sites in Imphal that the Japanese and the British skirmished in — the Japanese lost more than 30,000 men in a defeat so decisive that it ended their imperial pursuits in Asia. But it was only in 2013, when a vote by the National Army Museum of Britain termed them “Britain’s Greatest Battle” that the Battles of Imphal and Kohima entered public consciousness.

Till then, the battles were buried in the hills of the Northeast, unknown, save for some literature by military experts, war veterans and historians. In 2005, Rajeshwor chanced upon one such book: The Forgotten Army’s Box of Lions: The True Story of the Defence and Evacuation of the Largest Supply Depot on the Imphal Plain (2001) by Christopher D Johnson. “It was set in Manipur and focused on the battle of Kanglatongbi, I was surprised that I knew nothing about it. Growing up, we only knew what our grandparents told us…that there was a war…the Japan laan (war),” recalls Rajeshwor.

Over the years, he struck up an unlikely pen friendship with Johnson, whose father fought in the war. “Christopher started sending me books, war diaries — material I would devour late into the night,” he says. Soon, with Johnson’s cross-continental guidance and encouragement, Rajeshwor graduated from books to battlefields. “They were all around me . . . all these years, I had no idea,” he says.

In time, many friends joined in. Before they knew it, weekends or holidays became sojourns into history. “We would go from battlefield to battlefield, spades and shovels in hand. Even years later, there were things to find: helmets, shrapnel, cartridges, personal artefacts such as buckles and combs and even bones,” he says. In 2013, Rajeshwor and his friend, Arambam ‘Bobby’ Singh, founded the Second World War Imphal Campaign Foundation to formalise their weekend expeditions in digging up a forgotten battle. Since 2017, the Japan Association for Recovery and Repatriation of War Casualties has been collaborating with the foundation on missions to recover the remains of Japanese soldiers killed in the war. “But I am not allowed to talk about that,” says Rajeshwor.

What he can talk about are the personal requests he gets. Through Johnson, Rajeshwor was introduced to descendants of a number of war veterans seeking information about the last days of their family members. “It started with someone wanting me to lay a wreath at their grandfather’s grave in the Imphal Cemetery,” says Rajeshwor. Over the years, the requests became more elaborate: someone from the UK enquiring about the location of a tank blast their grandfather died in (“Could you please find that spot and lay a wreath there?”); another 78-year-old from the UK whose dying wish was to locate his father’s remains in Imphal. “I have done all that — climbed a hill, laid a wreath, put a poppy cross,” says Rajeshwor. When last June, Sharon Gibson, a 40-year-old nurse, reached out to him from Edinburgh, with a request to “find” her long-dead great-grandfather, with only a name (David Tod) and a photograph (black-and-white and faded), he told her: “No problem. This is a big thing for you, but a small thing for us. We will do it.”

When we reach the top, Rajeshwor and his team get to work at once — the metal detectors and shovels are out, tents are being pitched, wood is being collected to cook lunch, and “toilets” are being “constructed” — unperturbed by the fact that it is raining, a bitter cold wind sweeping away the glorious summer day we left behind at the base of the hill. The British codenamed it the Pimple (because it resembled one), and Rajeshwor and his friends refer to it by the same name.

It is a terrain he has studied for a year — first, through documents he sourced from the British Library, then through a drone he flew over it and by trekking to the spot last November. “We followed the exact route mentioned in the British war diary of the time. It maintained the events of the episode — who shot whom, the direction of the attack, etc,” says Rajeshwor. According to records, 16 Allied soldiers had fallen at the Pimple. “According to protocol, they were buried with crosses. But when the Imperial War Graves Commission unit came two years later to collect the remains, the area was an overgrown jungle and the markers were gone,” says Rajeshwor. “Of the 16 bodies, only 12 were recovered, and four were left behind.”

One of them was of Tod, Gibson’s great-grandfather. The family believed that he was “lost in the jungles of Burma (now Myanmar)”, since these battles fell under the British’s “Burma Campaign”. “That the battlefields transcended the boundaries of Burma is something they have come to understand now,” says Joseph Longjam, a Directorate of Information and Public Relation employee in Imphal, who works with Rajeshwor.

“We were really expecting a jungle in Burma and not a hill in Imphal,” says Gibson later, over an email. Last year, she dreamt of a man, who she thinks was her great-grandfather, telling her: “Find me in Burma.” Gibson got herself on a Facebook group, comprising families of war veterans, scholars and historians. Her queries led her not to Burma, but to a man in Imphal. That month, Rajeshwor pored over war diaries, got in touch with researchers in the UK and managed to track down Tod’s regiment, and, finally, the location where he died, by painstakingly superimposing map references of the time to Google Earth to pinpoint the rough location of 25 yards. Finally, in November last year, they did their first trek.

“We just started digging anyway in the location we identified. Suddenly, we found the personal effects of soldiers in a pit. For us, it was a eureka moment because it meant that the four remaining bodies were around that area,” he says. At Gibson’s request, Rajeshwor had lugged up a memorial plaque and a remembrance poppy cross. In a small ceremony, the team laid the plaque at the spot where they believed Tod was killed, and livestreamed it to her in Edinburgh. “It was a very emotional sight. I was afraid to even blink in case I missed any of it,” she recalls. “Rajeshwor dusted off the layers of time and brought a little-known part of history to light. It is amazing what he has done for me, a stranger from across the globe.”

ven before his first climb, Rajeshwor was certain about one thing: he wasn’t here to make money off dead people. The excavation expeditions involve trekking up various hills (the Pimple is one of the more accessible ones), arranging for food, shelter and equipment for digging — but they are funded entirely by the members.

“While Sharon did insist on paying for the memorial plaque, I did not charge her for anything else. I do not want to earn a single penny off this,” says Rajeshwor, after a long day of digging. At night, a small bonfire has been lit, a few glasses of rum are had before a dinner of pork, rice and boiled vegetables.

“For me personally, I do not care much about historical dates,” says Longjam, the DIPR employee, “Jo ho gaya so ho gaya. But if what we do makes people visit Imphal, it means a lot.”

In recent years, Manipur has seen the beginnings of “war tourism” — initiatives to map the war through battlefield tourism tours, perhaps the first of its kind in the country. “WWII battlefields in Europe are mapped to the T; the Indian part of the war and the sites of fighting around Manipur and Nagaland have always been hazy,” says researcher and author Hemant Singh Katoch, on the phone from Yangon. In 2013, he founded and conceptualised the “Battle of Imphal” tours, the first in the state. In the three years he spent in Imphal, Katoch led many tourists — often families of war veterans — on these tours. “It is a way to connect to their family’s past. In some cases, it is not a grandfather or granduncle, but the father who has fought the war.”

For example, Johnson has spent decades unravelling his father George Johnson’s role in the war. He tracked down families of those who served with his father in Imphal. In time, he found out that George had to kill one of his wounded orderlies, Howard, in the war. “It was a case of mercy killing — my grandfather never spoke about it, but carried with him years after the war,” says David Westgate, Johnson’s nephew, over a video call Rajeshwor sets up for me that night from the hill.

In 2017, Johnson managed to track down Howard’s family, and in April last year, during the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Imphal, his great granddaughter, Ellie, flew down to Imphal. “We were there too, and with Rajeshwor’s help we had a small funeral ceremony, bugles and all, where her grandfather died,” recalls Westgate. “I don’t mind admitting it but I started crying. I walked up to her and apologised. She told me, there was no need to say sorry. ‘Your grandfather did what he had to do.’”

“Searching for a person’s remains is like looking for a needle in the proverbial haystack,” says Rajeshwor, leaning on his spade. The next morning, the hill is abuzz with the beep-beep of metal detectors, and the scraping of shovels. Around Rajeshwor, are Longjam, and Ratan, both longtime members of the group. “All these years, we have not recorded our work but I am thinking of making a video repository on YouTube and naming the channel ‘Battlefield Diggers’,” says Rajeshwor.

“We have never felt the need to,” says Longjam, “Our satisfaction comes from connecting people to their forefathers. Some families just want to know where their fathers or grandfathers went, what kind of places they stayed at, what they did. For them, this is a part of the world they know very little about.”

Last October, the team chanced upon a mass burial site, the recovered remains of which they have handed over to the Japanese. “But personal bone collection missions, like that of Sharon’s great-grandfather, can take years too,”says Rajeshwor.

At the end of the dig, they have shrapnel, a few buckles, a comb, parts of a bullet, tail fins of mortar shells, but no bones. Before the team starts their descent down the Pimple that afternoon — unaware that a pandemic will keep subsequent ones on hold for some time —Rajeshwor calls up Gibson, and informs her that the excavation was unsuccessful.

“That’s okay,” she says, “At least, we now know where great-grandfather Tod is. He is no longer lost.”