SOURCE: MONEY CONTROL

Tens of thousands of people marched, one grey spring morning in 1990, to the Eidgah in Srinagar to bury Ashfaq Majeed Wani, then the icon of the Kashmir insurgency. Wani’s claims to this honour were dubious: He’d kidnapped former Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti’s sister, and menaced the Pandit minority, before ending his career by accidentally blowing himself up with a grenade in a botched ambush near Srinagar’s Firdaus Cinema—the only actual military operation he participated in.

In 1990, even a second-rate martyr sufficed. “Mothers would put mehendi on their sons going to Pakistan”, recorded the scholar Navnita Behera. “Children carried placards saying ‘Indian dogs go home’ or ‘Mujahideen qaum zindabad’”.

This week, following the killing of Hizb-ul-Mujahideen Kashmir division chief Riyaz Naikoo, it’s become the rage that drives this impulse are still alive. The gaggles of young people who turned out throw stones at police after his killing were small—faux editions, as it were, of the huge crowds that turned out for Wani, or in 2016, for that other jihadist icon, Burhan Wani—but there’s no mistaking their significance.

Labouring under the delusion that the termination of Kashmir’s special status would annihilate the ethnic-religious nationalism that has long driven the jihad, New Delhi’s reverie is now being rudely interrupted by reality.

The de-operationalisation of Article 370 in August had its genesis in 2016, when the killing of Burhan Wani unleashed a great tide of Islamist-led protest swept aside the Indian state, and established something resembling de-facto independence. Chief Minister Mufti’s government proved unable to reestablish order—eventually leading New Delhi to impose central rule, and then, on the back of the most severe political restrictions seen in India since the Emergency, restructure Kashmir’s constitutional relationship with India.

Now, as New Delhi cautiously eases the lockdown imposed in August, and moves towards normalisation, it’s clear little has changed: local recruitment of jihadists has resumed, street violence has reappeared, and levels of terrorist violence have slowly begun to climb. Large Islamist-led gatherings at the funerals of jihadists have even forced the government to take the extraordinary step of ceasing to hand over their dead bodies to their families.

Levels of violence aren’t anywhere near high enough to provoke panic. But New Delhi needs to be asking itself if the time hasn’t come to look beyond purely coercive tools, like internet shutdowns and restrictions on political activity. The status quo, New Delhi understands, is unsustainable—but to move forward, the government needs to start looking beyond its nose.

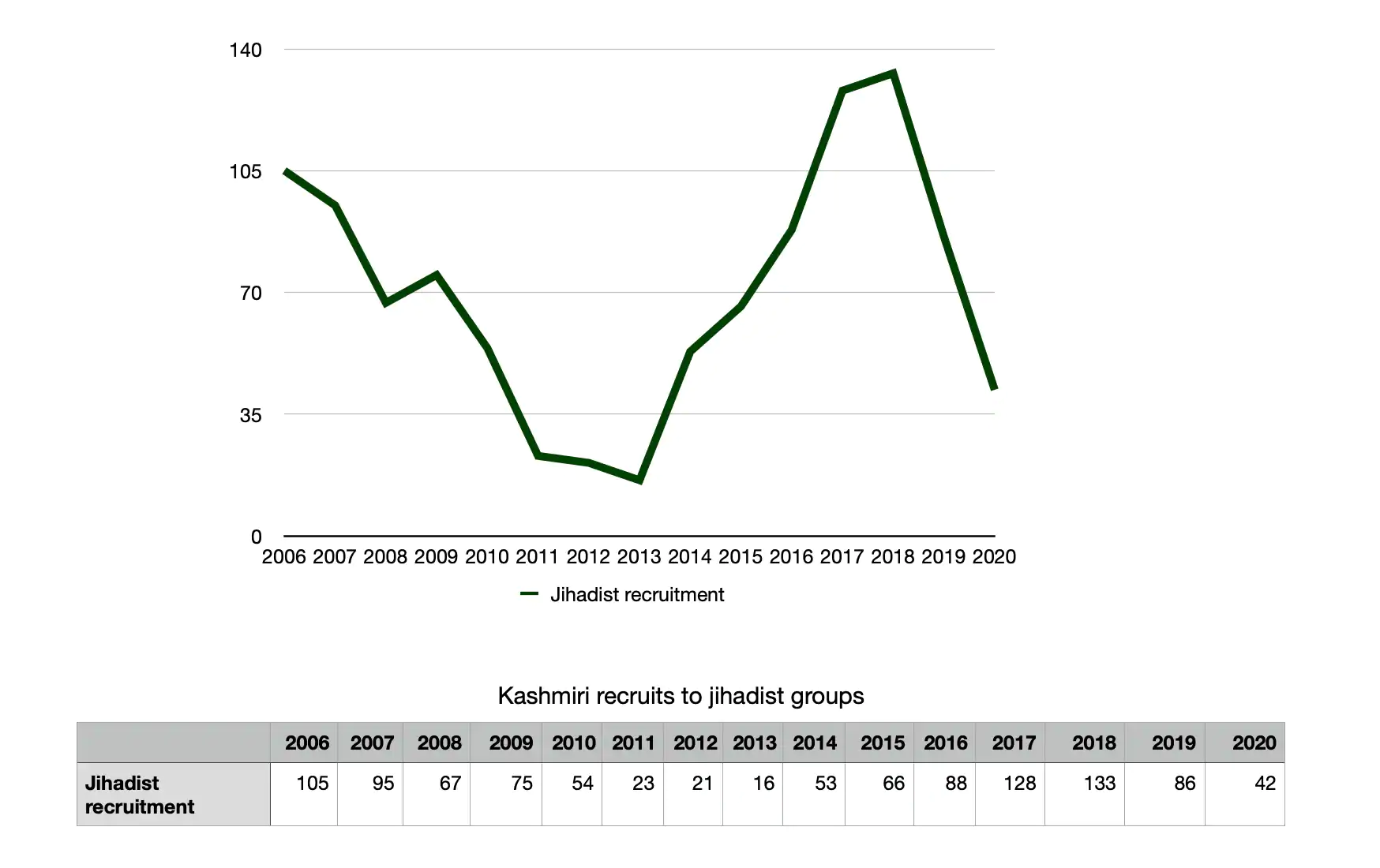

To begin with, some introspection on how the crisis of 2016 was engendered is critical. From 2006 to 2013, government data shows, recruitment of ethnic Kashmiris into jihadist groups fell to near-zero levels—this despite the murderous, communally-charged street violence of 2008 and 2010, which claimed the lives of hundreds of young men who battled police.

From 2014 on, though, the numbers began to rise—the consequence, it’s likely, of mounting fears over the power of Hindu nationalism in India. Paranoia about evil Hindu-nationalist plots to displace Islam from Kashmir has a long and sordid history in the state’s politics.

Kashmir’s Muslims had watched the Partition massacres in Jammu—and looked at India with fear. “There isn’t a single Muslim in Kapurthala, Alwar or Bharatpur”, Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah said. Kashmiris, he recorded, “fear the same fate lies ahead for them”. Abdullah worried that the Hindu right-wing would one convert India “into a religious state wherein the interests of Muslims will be jeopardised”.

Through the 1970s, amidst periodic explosion of violence, the Jamaat-e-Islami even claimed the government had set up a team “to investigate how Islam was driven out of Spain and to suggest measures as to how the Spanish experiment could be repeated in Kashmir”, scholar Yoginder Sikand has recorded.

And, at a March 1987 rally in Srinagar, Muslim United Front candidates, clad in the white robes of the pious, declared that Islam could not survive under the authority of a secular State.

Faced with the rise of prime minister Narendra Modi’s government, the National Conference government tried to cash in. Political Islamists were given space; aggressive counter-terrorism action reined in. In 2015, tens of thousands were allowed to assemble for the funeral of Lashkar-e-Taiba jihadist Abu Qasim—the first such display of support for a Pakistani jihadist, and a turning point in Kashmir’s history.

Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti’s PDP government also sought to accommodate this ethnic-religious paranoia, rather than confronting it. The government allowed New Islamist youth leaders grouped around secessionist patriarch Syed Ali Shah Geelani—notably Masrat Alam Bhat and Asiya Andrabi—free reign, and reined-in police action against ground-level organisers of the religious right. The party hoped that by doing so, it would deflect criticism from Islamists that its alliance with the BJP had opened the door for ethnocide.

Legitimised heroic defenders of Kashmiri Islam against a predatory Hindu nationalism, a new generation of jihadists began to join the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen and Lashkar-e-Taiba—leading up to the crisis of 2016. Few of these young recruits, unlike their predecessors of the 1990s, had any form of military training; as fighters, they were largely ineffectual. But Burhan Wani or Riyaz Naikoo were significant not for what they did, but as an aesthetic.

Kashmir’s historically-unprecedented youth male cohort has found a new vocabulary, in neo-fundamentalist Islam drawn off the internet. Islamist currents have long existed in Kashmir. The Jama’at Ahl-e-Hadis, established in Kashmir in 1925, and the Jama’at-e-Islami, wielded great influence over the jihadist movement. The new youth cohort, though, has borrowed the aesthetics of neo-fundamentalism without the rigours of membership of these parties. Internet Islamism appears to offer a kind of moral liberation, free from the taint of compromise.

Ever since 2006, thus, young people have found agency around aesthetic questions: Faith, religious identity, issues of honour, particularly the protection of women’s chastity. This is the classic material of ethnic-religious nationalist movements, Islamic, Hindu or otherwise. Young people attacking the police find a sense of agency, even heroism, in giving their blood to guard Kashmir’s cultural and religious identity against what they imagine to be predatory Hinduism.

Like elsewhere in India, the tide of religious fundamentalism in Kashmir has flourished in a landscape characterised by high levels of youth unemployment and lack of economic opportunity.

Politicians have betrayed this generation more than once “Give me five years of peace”, CM Mehbooba Mufti said at a rally in Udhampur in April, “and I will give you development”. Her predecessor, Omar Abdullah, often said much the same thing. “People have to decide how long they will wait for peace and prosperity”, he proclaimed in Sopore in 2013, at a rally in the Islamist heartland.

In 2006, an expert task force appointed by then PM Manmohan Singh made several recommendations to address the firmament on which Kashmir’s youth crisis rests, proposing radical initiatives to develop linkages between agriculture and industry, train young people for opportunities in the services sector, offer land to business, and build a new satellite city for Srinagar.

Barely a single recommendation has been implemented—so it’s no surprise Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s promises of building a new Kashmir have been greeted with scepticism. The state’s moribund bureaucracy, whose incompetence has survived changes to its constitutional status unscathed, hasn’t helped matters. Neither has New Delhi’s vacillation over protections of state residents’ land-rights and employment prospects.

For Pakistan, this has meant opportunity. Conventional wisdom has it that Pakistan Army firing across the Line of Control is intended to facilitate infiltration, since it compels India’s troops to take cover. The proposition is borne out by the government’s data for 2014-2017, which shows infiltration marching in lock step with the level of fire exchanges between Indian and Pakistani soldiers stationed on the Line of Control.

In 2018, though—the year Imran Khan became prime minister of Pakistan—something odd happened. Even though cross-border fire escalated to the highest levels since India and Pakistan entered into an—unsigned—ceasefire, infiltration began to decline, and has continued to diminish.

The likely explanation is that the Pakistan Government wants to avoid risking war by significantly raising support for Kashmiri jihadists—a risk hammered home by the Pulwama crisis in 2019.

Little imagination is needed to see that the status quo serves Pakistan’s interests. Enhanced local recruitment of jihadists, and the rising tempo of street protest, might serve little military purpose—but they serve to discredit India’s claims that Kashmir is limping back to normalisation. They also complicate India’s efforts to initiate a political process in the state.

Prime Minister Imran Khan and the country’s all-powerful army, meanwhile, are able to use the continued tensions along the Line of Control to advertise their commitment to Kashmir to a domestic audience—without actually taking the risks that would come with significantly escalating support for jihadists.

For New Delhi, therefore, the grim impasse in Kashmir is the worst of all possible worlds. The Union government would do well to begin a serious dialogue with political forces in and outside the state on what a meaningful way forward might be.

https://defencenewsofindia.com/in-kashmir-new-delhi-needs-to-look-beyond-its-nose/