SOURCE: THE PRINT

It has been nearly two weeks since India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi reached a five-point consensus on de-escalating tensions along the Line of Actual Control. But there seems to have been no movement towards disengagement on the ground in eastern Ladakh yet.

The two countries issued a joint statement Tuesday evening, after the sixth round of military commander-level talks the previous day, in which they agreed to stop sending more troops to the frontline, refrain from unilaterally changing the situation on the ground, and avoid taking any action that may complicate the situation.

The India-China standoff has been continuing since April-May, and took another turn earlier this month when shots were fired along the Line of Actual Control for the first time in 45 years. Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s statement in Parliament last week was the government’s first formal, high-level statement on the standoff. He said the India-China relationship could not progress if there was trouble and instability on the border, but also blamed China for violating past protocols when it moved large bodies of troops, equipment and ammunition to the LAC in April.

An unusually candid Rajnath also said there was no commonly delineated LAC and that China did not recognise traditional or geographical boundaries. His statement just went to show how complicated the situation at the LAC in eastern Ladakh really is. ThePrint tries to simplify things with the help of a few maps of the region.

Depsang Plains

While the Chinese incursion into Indian territory began in April (see map above), the People’s Liberation Army had started transgressing key points in the Depsang Plains much before.

The Depsang Plains, located in the northern part of eastern Ladakh, are close to the strategically important Daulat Beg Oldie (near the Karakoram Pass), where India’s highest airstrip is located. The plains come under India’s sub sector north (SSN), and lie between the Siachen Glacier on one side and Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin on the other.

For months now, China has been denying Indian troops access to patrol points 10 to 13 in Depsang from a strategic bottleneck called the Y junction.

Defence sources say China is blocking Indian soldiers’ access to a large tract of land, which adds up to 972 square kilometres.

While the main flashpoints of the India-China tension lie further south, including the heights and other features near Pangong Tso, satellite images have shown an additional deployment of troops from both sides at the Depsang Plains. The Chinese have deployed additional tanks and artillery guns and moved them forward from their usual positions, while India has deployed additional men, tanks and other equipment into the area in response to the build-up.

As reported by ThePrint, the tensions in the Depsang Plains go back to China’s 18-km incursion into the area in 2013, followed by the 2017 Doklam standoff near India’s tri-junction with China and Bhutan to the east.

In 2013, despite talks in which both India and China agreed to go back from their positions, PLA troops never went back completely across what India perceives to be the LAC.

India has created a separate brigade to look after the SSN following 2013.

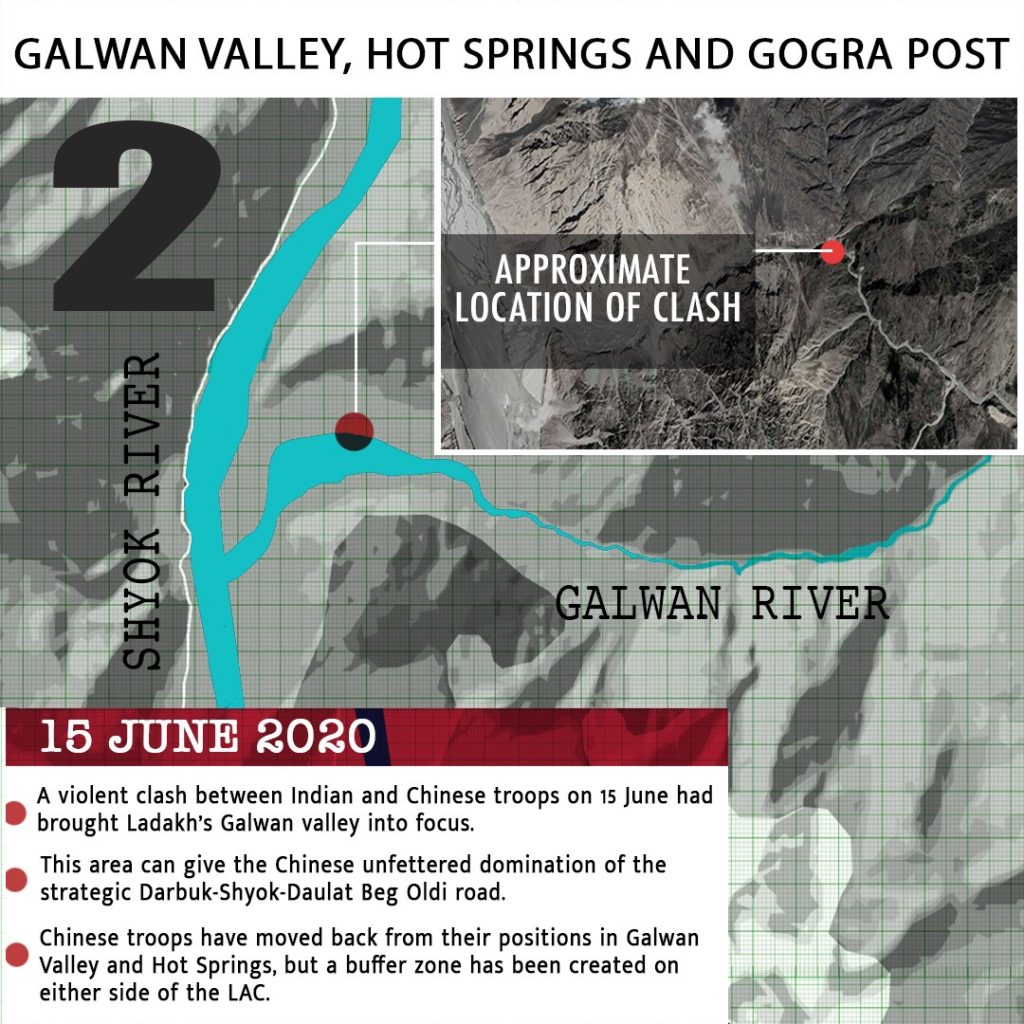

Galwan Valley, Hot Springs and Gogra Post

A violent clash between Indian and Chinese troops on 15 June had brought the Galwan Valley into focus. The violence, in which no firing took place, killed 20 Indian soldiers, including the commanding officer of 16 Bihar, Colonel Santosh Babu.

Sources said this area could give the Chinese unfettered domination of the strategic Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DS-DBO) road. “The Galwan clashes were an attempt by the Chinese to dominate these areas,” a defence source told ThePrint.

It is for the same reason that the Border Roads Organisation has stepped up work on an alternate route to DBO, which will run along the Nubra river to the vital locations of Sasser La and Gapshan before joining the existing DS-DBO road.

Since the incident and multiple levels of military and diplomatic talks, Chinese troops have moved back from their positions in Galwan Valley, but a buffer zone has been created on either side of the LAC. As a result, Indian troops are not able to access patrol point 14.

At Hot Springs and Gogra Post, however, Chinese troops have not fully pulled back, and have left some elements behind.

India continues to carry out constant surveillance of the area. Additional troops have been deployed along the DS-DBO road, which passes close to the Galwan Valley, for faster movement of reserves and a quicker response in case of an operational requirement.

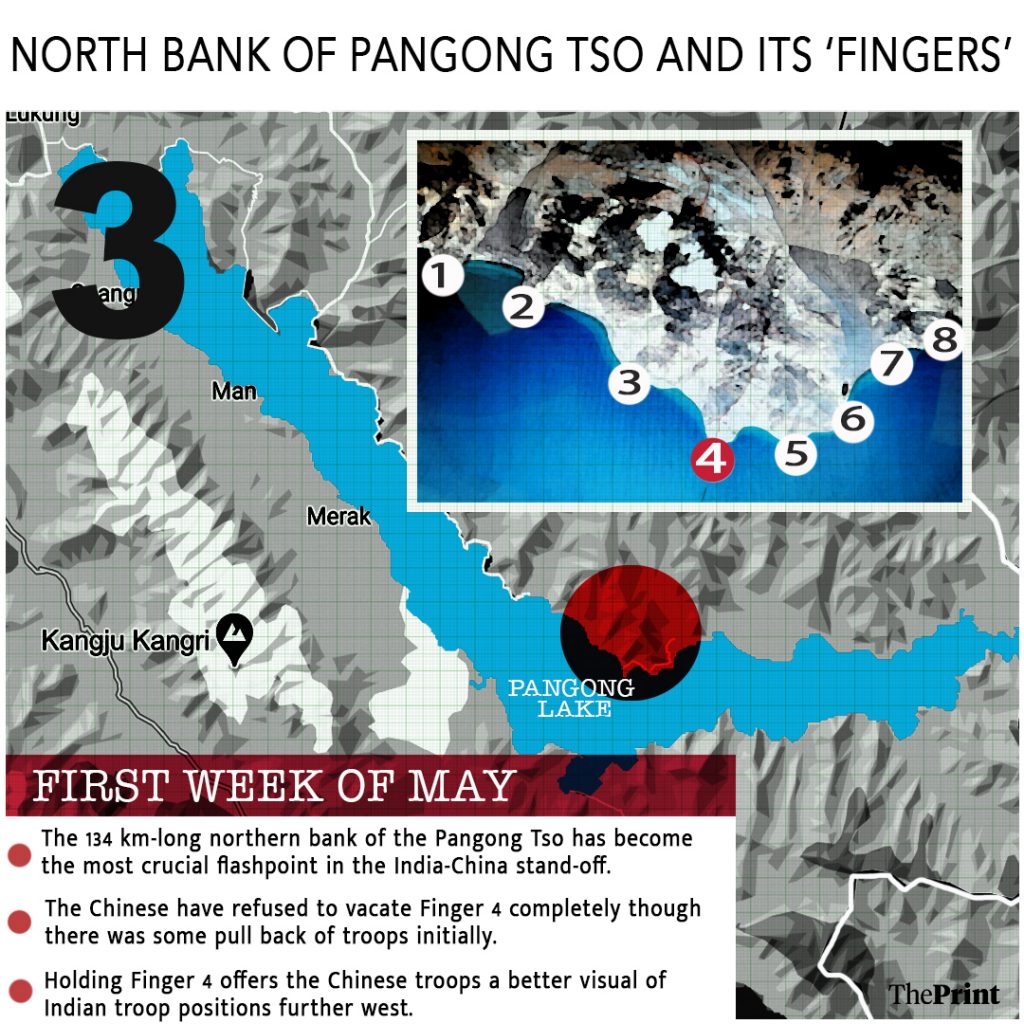

Northern bank of Pangong Tso and its fingers

The 134-km-long northern bank of the Pangong lake has turned out to be the most crucial flashpoint in the current standoff.

The northern bank juts out into the lake like a palm, and the various protrusions or mountain spurs are identified as ‘fingers’ to demarcate territory.

While India asserts that the LAC lies at Finger 8, China claims it starts at Finger 2, which India dominates.

Since the beginning of the standoff, China has come to dominate the area between Finger 4 and Finger 8, a distance of about 8 km, which India has repeatedly asserted lies on its side of the LAC.

Defence officials said while China committed to pull back its troops after the military-level talks between the two sides, they have refused to vacate Finger 4 completely, though some troops were pulled back initially.

Sources say holding Finger 4 offers the Chinese troops a better visual on Indian troop positions further west. As a result, the talks between the two sides also hit a roadblock and reached an uneasy stalemate before Indian troops captured some key heights on the southern bank of Pangong Tso, pre-empting Chinese military mobilisation near the Spanggur lake.

This move, sources had said, gives better bargaining power to the Indian side during talks.

The situation at Finger 4 is tense after Indian Army troops took control of heights overlooking Chinese army positions.

Just before Jaishankar and Wang Yi’s meeting in Moscow on 10 September, multiple rounds were fired in air by troops on both sides at the overlapping heights of Finger 3 and 4, making it the second such incident at the LAC in 45 years.

Southern bank of Pangong Tso

The latest flashpoint in the tensions saw the Indian Army occupy key heights on the southern bank of Pangong Tso. This is where Chinese troops are said to have fired shots for the first time in 45 years.

Indian and Chinese troops were at a distance of barely 300 metres from each other, with a group of 40 Chinese soldiers staying put at one location, sources said.

Aside from firing, Chinese troops at some places had also moved in with clubs, machetes and spears among other sharp weapons — similar to what they carried during the Galwan clash on 15 June. The Chinese have deployed tanks and artillery guns near the Spanggur Gap. India has also put in place troops and equipment to counter the Chinese deployment.

Sources said the southern bank of Pangong Tso emerged as a new front after Indian troops pre-empted Chinese military mobilisation and occupied around 30 dominating heights and terrain features close to the LAC — including Rezang La, Rechin La and Magar Hill among others — on 29-30 August. There were reports of action at a feature called Black Top too, but sources in India’s defence and security establishment underlined that the forces had not crossed the LAC.

The southern bank also gives the Indian troops an advantage in terms of monitoring activities on the northern bank of the lake.