SOURCE: INDIA TODAY

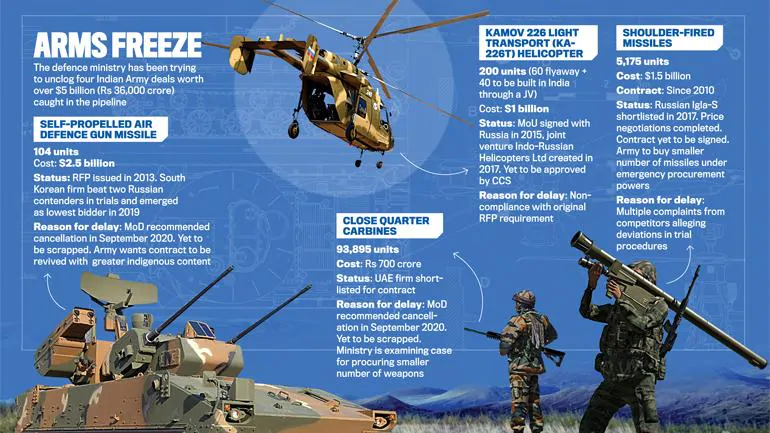

Four big-ticket Indian Army procurements for carbines, mobile air defence gun-missile systems, light helicopters and shoulder-launched missiles worth over $5 billion (Rs 36,000 crore) have been caught in an impasse for several months now. But for the ongoing military standoff with China, delays in acquiring this urgently required hardware would not have spelt a crisis. This is because India’s process-driven defence acquisitions move at a snail’s pace, with each contract taking an average 7-8 years to be concluded.

These four cases are only part of the Rs 90,048 crore the ministry of defence (MoD) plans to spend on buying new hardware for the forces in the present financial year, minister of state (MoS) for defence Shripad Naik told the Lok Sabha on September 15.

Two cases are particularly urgent as they are meant to replace the army’s vintage in-service military hardware. The army’s 1970s model Cheetah helicopters used to resupply troops in high altitudes at Siachen and Ladakh and the dwindling stock of shoulder-fired missiles meant to provide low-cost air defence solutions, particularly in the frontlines, are nearing the end of their lifespans. The army needs new air defence gun-missile systems to replace the World War II-era L-70 guns. For three of these imports, light helicopters, air defence guns and carbines, we have indigenous alternatives which are fit cases for the government’s ‘Aatmanirbhar Bharat’ initiative. Yet, these deals, held up for reasons ranging from deviations in procedure, budgetary constraints, complaints from competitors and a recent renewed thrust for indigenisation, have become a sort of Gordian knot the ministry seems unable to slice through. Adding to the difficulties is the looming shadow of India’s largest arms supplier and strategic partner Russia. Russian state-owned firms are in the fray for three of the big-ticket items and Moscow is believed to have lobbied for stalling the deals at the political level. The UAE government, another country with significant diplomatic heft in New Delhi, owns the firm in the fray for carbines. The defence ministry has held a series of recent meetings to resolve the intractable delays in these cases, but without much success.

The eternal loop

On September 15, the defence ministry made its most determined effort to ‘un-jam’ three of these procurements. A meeting attended by chief of defence staff Gen. Bipin Rawat, in his capacity as secretary, department of military affairs, vice-chief of army staff (VCOAS) Lt Gen. S.K. Saini and top MoD officials took some swift decisions. It decided to scrap the imports of over 93,000 carbines from UAE’s Caracal International LLC (the shortlisted firm) and the self-propelled air-defence gun missile systems (SPADGMS) for which South Korea’s Hanhwa Defense had emerged lowest bidder. The carbine deal was scrapped because only one company qualified, an undesirable ‘single vendor situation’; the air defence system because of complaints from the Russian competitor alleging deviations in trials.

Over a month later, however, both deals continue to be in limbo and are yet to be scrapped because the army is keen on going ahead with the procurements. Caracal, a subsidiary of the UAE government-owned EDGE group, has now offered local production (earlier all the weapons were to be imported from the UAE under a fast-track procedure). A key defence ministry official has recommended a smaller, off-the-shelf buy of around 25,000 carbines. The army has been advised to extend the life of its 2019 ‘acceptance of necessity’ given for an order of 350,000 carbines to ‘buy and make’ the weapons in India. The MoD-owned Ordnance Factory Board and private companies like Adani Defence and SSS Defence are in the fray.

It is in the case of the gun-missile system that the delays could be protracted. The army had in 2013 floated a requirement for five regiments of a self-propelled air defence gun-missile system. The 104 units were budgeted at approximately $2.5 billion, with each unit having twin 30 mm cannons and four short-range missiles fitted on a tracked chassis. These self-propelled gun-missile systems are meant to protect vital areas and installations from threats like low-flying aircraft, helicopters and drones. South Korea’s K30, made by Hanwha Defense, emerged as the lowest bidder beating out two Russian contenders. Cost negotiations did not proceed after the Russian side objected to their exclusion from the deal. The defence ministry recommended that the deal be scrapped on the grounds that the army’s specifications for the contract, dating back to 2011, were nearly a decade old. Hanwha has now offered maximum indigenisation in manufacturing, assembly and integration at existing facilities of Larsen & Toubro or other Indian defence companies, government sources said.

The MoD is also trying to revive a stalled joint Indo-Russian deal to jointly manufacture 200 Ka-226T helicopters. The deal was part of an inter-governmental agreement (IGA) signed in Moscow in 2015 during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s summit visit with Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), Russian Helicopters and Russia’s state arms exporting firm Rosoboronexport formed a joint venture, Indo-Russian Helicopters Ltd (IRHL), in 2017 with a holding of 50.5 per cent, 42 per cent and 7.5 per cent, respectively, but the deal has not progressed because the MoD has flagged a serious divergence in procedure. The deal has been found to be non-compliant with the original requirement of the request for proposal (RFP)—that the indigenous component must be 70 per cent. The helicopters currently have 70 per cent Russian components and 26 per cent French (the engines). IRHL has said it can achieve 70 per cent indigenous components only in the fourth and final batch of helicopters. Delays in this deal have been a recent bugbear in defence ties between India and Russia and the MoD has suggested that the case be fast-tracked. Government officials say that the army, HAL, IRHL and the MoD have concluded that Russia needs to increase the indigenous content in the helicopters and also transfer critical technologies.

The MoD has two alternatives: altering the RFP requirements, or scrapping the deal altogether. The former would need fresh approvals from the defence acquisition committee (DAC) headed by defence minister Rajnath Singh; scrapping the deal could be difficult since it was part of the 2015 Modi-Putin IGA. But it wouldn’t be the first time India has walked out of similar JVs. In July 2018, then defence minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the government was backing out of the Indo-Russian Fifth General Fighter Aircraft (FGFA) project. The reasons had to do with an increase in costs and the IAF and HAL’s unhappiness with the technology being shared.

If the MoD does walk down a similar path with the Ka-226T, it has the homegrown Light Utility Helicopter (LUH) to fall back on. The LUH, designed and built by HAL in a short span of five years, demonstrated its ability to operate in high altitudes in September this year. During 10-day trials, the machine flew from Leh and did a ‘hot and high’ hover performance at the Daulat Beg Oldie advanced landing ground which, at over 16,000 feet, is the world’s highest. HAL officials say the helicopter also demonstrated its payload capability at the Siachen glacier. HAL CMD R. Madhavan says the army version of the LUH is now ready for initial operational clearance (IOC). Government sources, however, say that the LUH’s slow rate of induction will not be able to meet the army’s needs. “Meeting our requirements in an acceptable time-frame dictates dual route induction of Ka-226 T and the LUH…it was a conscious decision taken back in 2015,” says a government official.

The Russian missile

In February this year, Gorgen Johansson, president of Saab Dynamics AB, wrote a letter to Rajnath Singh. The chief of Sweden’s largest defence firm made serious charges against Russia’s Rosoboronexport which had emerged lowest bidder in the Indian army’s decade-old search for a new shoulder-fired air defence missile. Johansson said that the Russian firm ‘had repeatedly been given undue advantages outside the perimeter of the defence procurement procedure’ and hence should have been disqualified. The Russian military was replacing the Igla-S with a newer missile, the Verba, Johansson said, and hence India would not get the benefit of state-of-the-art technology. The letter, which is the second one in two years from the Swedish firm, has put a spoke in the procurement of what the army calls an urgent operational requirement.

The army’s search began way back in 2009 with an AON (acceptance of necessity) to buy 5,175 VSHORAD (Very Short Range Air Defence) man portable systems. The missiles were categorised a ‘Buy and Make’ deal in which the lowest bidding foreign vendor would supply an initial lot of missiles and equipment and transfer technology to an Indian public sector undertaking to manufacture the remaining missiles locally with full transfer of critical technology like the booster and seeker. The deal has been mired in controversy ever since the five-year-long field trials of three missile systems, French, Swedish and Russian, concluded in 2017. Saab’s first letter alleging deviations in trials favouring the Russian side was sent in 2018. An MoD-appointed committee that year did not see any deviations in procedure and gave the deal the go-ahead. Fresh complications have arisen with the Russian side refusing to transfer booster and seeker technology. The 2020 letter from the Swedish firm, however, has stalled the deal as the ministry looks for ways to overcome this. One option is to buy a limited number of missiles off the shelf under the fast-track procedure and explore indigenous options later. But unlike the HAL-built light helicopter which can be brought to service within five years, there is no swift indigenous solution here. The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) has made promises of delivering a man-portable missile in three years but it needs to convince the army that it can do so within the time-frame. The army is procuring a certain quantity of lgla-S missiles through the Rs 500 crore emergency powers route delegated to the VCOAS.

Needed, a holistic reassessment

Many of these deals have been in the pipeline for close to a decade and from a time when it was assumed defence budgets would increase to keep pace with the growing requirements of the forces. Meanwhile, the standoff in Leh has refocused the army’s efforts towards a whole new set of hardware requirements, from drones capable of operating at high altitudes to weapons that can shoot down enemy drones to sensors that can look deep across the LAC in all-weather conditions. It remains to be seen if the army’s already constrained budgets will permit these newer acquisitions as well as replace its legacy systems in a unit-for-unit case. “We require a de novo joint service capability review to remove irrelevant procurements, duplication or multiple inventories,” says Lt Gen. A.B. Shivane, the army’s former DG, Mechanised Forces. Such a capability review would notice, for instance, the multiple inventories created if the MoD went ahead and bought both the Ka-226T and the indigenous LUH, creating two separate production lines for a machine essentially meeting the same requirement. As always, there are no easy solutions without a deep reform of the procurement system.