INS Vikramaditya, India’s only aircraft carrier, which would be joined this month by the new INS Viraat

By Vikas Gupta

Trade standard

August 15, 2022

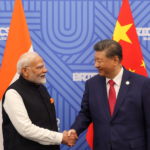

Last week, an opinion column in this newspaper argued for the speedy construction of a second indigenous aircraft carrier (IAC-2) for the Indian Navy. The first indigenous carrier, IAC-1, which was built by Cochin Shipyard Ltd, will soon be commissioned as INS Vikrant. Alongside INS Vikramditya, acquired from Russia in 2014, the Navy will then operate two 44,000-ton aircraft carriers.

The proposed 65,000 ton IAC-2, which would take at least another decade to build, would be the third carrier in the fleet. With one of them under repair or refit at any given time, the Navy would always have two aircraft carriers available and ready for operations.

The measure of an aircraft carrier’s power is its air wing. A carrier takes on board approximately one aircraft for every 1,000 tonnes of displacement. Vikramaditya and Vikrant both displace 44,000 tons, each carrying 25-30 fixed-wing aircraft, as well as 10 helicopters of various types. The planned third carrier – the 65,000 ton IAC-2 – would pack significantly more air power. He would go into battle with 54 fighters (three squadrons of 18 fighters each), enough aircraft for fleet air defense, as well as land strikes.

Additionally, IAC-2 would carry around 10 helicopters, for anti-submarine warfare (ASW), airborne early warning (AEW) and casualty evacuation duties. Its larger size would also allow it to carry airborne early warning (AEW) tactical aircraft, such as the Northrop Grumman E-2C Hawkeye – an invaluable asset in the air battle.

IAC-2 would be quite imposing based on its full air power alone. But, in fact, IAC-2 would not fight alone. It would be the flagship of a carrier battle group (CBG) which would also include submarines, destroyers, frigates and corvettes, in addition to its own armament. These capital warships would give the CBG tremendous anti-submarine, anti-surface, and anti-aircraft firepower.

Still, there are several reasons why the Ministry of Defense (MoD) did not order the construction of the IAC-2. First, there is no consensus within the military on the need for a third carrier. The proposal to build one was publicly questioned by former Chief of the Defense Staff (CDS), General Bipin Rawat; and by successive heads of the Indian Air Force (IAF). Given this opposition, the navy has a difficult task to convince the other two services, as well as elements of the navy itself, that India needs an expensive third major carrier.

If you can’t lose it, you can’t use it

Secondly, the Navy faces a major hurdle in securing the necessary budget for what critics are now calling a ‘100,000 crore rupee carrier’. In fact, this figure is exaggerated. The cost of IAC-1 came to around Rs 20,000 crore; and the cost committee of the Ministry of Defense set the cost of the IAC-2 at Rs 40,000 crore. This takes into account the IAC-2’s larger size (65,000 tons, compared to INS Vikrant’s 44,000 tons), its more sophisticated and expensive weapons and sensors, and inflation.

The alleged figure of Rs 100,000 crore also includes the cost of an entire air wing including fighters, helicopters and combat support aircraft. The Navy will already have paid for two air wings – 45 MiG-29K/KUB fighters were purchased a decade ago, while another 57 multi-role carrier-based fighters (MRCBFs) are being acquired. Since only two CBGs would be sailing at any given time (with the third carrier in the shipyard), the Navy only needs two air wings, not three.

India’s tri-service planners believe that the MRCBFbeing evaluated for aircraft carrier deck operations – Boeing’s F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and Dassault’s Rafale – have only one “llimited affordability. This leads to a “we can’t afford to lose it” mindset and, therefore, to the conclusion: “we can’t afford to use it”. The Navy should only acquire platforms it can afford to lose and therefore use.

Third, the Navy recklessly adopted the British and French notion that carriers must be 65,000 tons of muscle for the traditional carrier mission of gaining sea control over a designated ocean space. Instead of starting with size, naval planners must first identify the carrier’s operational role. This stems from the National Security Strategy (NSS), which is overseen by the National Security Council. The NSS dictates the carrier’s mission capabilities, from which emerge its size, design, weapons and sensors.

Instead of this spin-off process, South Block planners pledged to follow the advice of a US-India “joint working group” (JWG) on carrier design. This moves forward with a US Navy-style “power projection carrier” that boasts formidable airpower, as well as surface and submarine strike capability within the CBG. There was little consideration of whether the Navy’s needs would be better met by a French-style “attack carrier”, which had an air wing built around the Etendard surface-attack aircraft. /Super Etendard, with some F-8 Crusaders for the fighter type. roles that involved protecting the attack aircraft.

The French “strike ashore” model is relevant to the Navy, as one of its key objectives is to maintain service relevance by influencing the all-important land battle. The new French carrier, Charles de Gaulle,serves this purpose by carrying the Rafale multirole fighter, which has both air defense and land strike capability

The Technology Outlook and Capabilities Roadmap 2018 (TPCR-18), which projects future weapon profiles, says nothing about what kind of carrier the IAC-2 should be. All the TPCR-18 says is: aircraft carrier, quantity 01.

Ignore an aircraft carrier pedigree

Fourth, the Navy has failed to live up to its 60-year pedigree of carrier operation. The IAC-1 and INS Vikramaditya are expected to carry at least 44 aircraft, going through the benchmark of one aircraft per 1,000 tons of carrier. However, both ships fall short of this benchmark because the Navy, unaware of its own design capability, contracted a Russian design bureau for the design of the aeronautical complexes of INS Vikramaditya and IAC- 1.

Fifth, Indian test pilots complain that the Navy blindly accepted US claims that the E-2C Hawkeye cannot be launched from a ski jump. They say American companies have a vested interest in perpetuating this myth, in order to put a catapult as a launch system on IAC-2.

Perfected by the United States Navy since World War II, a conventional catapult features a steam-powered piston system along the flight deck, which “catapults” the aircraft at 200 kilometers per hour, fast enough to to take off.

The catapult the Indian Navy is considering for IAC-2 uses a powerful electromagnetic field to accelerate the fighter to take-off speed. Developed by General Atomics and called the “electro-magnetic aircraft launch system” (EMALS), it equips the latest US Navy aircraft carriers, starting with the USS Gerald R Ford.

The two current Indian carriers operate as STOBAR ships (short takeoff but recovery arrested), but it remains to be decided whether IAC-2 would be a STOBAR carrier or a CATOBAR ship (catapult assisted takeoff, but recovery arrested). The possibility of putting an EMALS-assisted CATOBAR system on IAC-2 is under discussion within the JWG.

Finally, the size and specification of the IAC-2 would depend on whether the Indian Navy plays an operational role for the two-seat Super Hornets, which would justify adding the additional crew requirements that would be needed.

It should be noted that the Defense R&D Organization is developing the Indigenous Bridge-Based Twin-Engine Fighter (TEDBF) as a single-seat fighter. The future lies in “manned-unmanned teaming” or (MUM-T), which is the joint operation of manned and unmanned airborne assets (UAS) toward a shared mission objective.

The MUM-T drone is increasingly seen as one of the key innovations that will define future airpower. The system will integrate intelligent, connected and modular UAS, linked by a distributed intelligence network that will act as force multipliers for the piloted aircraft. Overall, it is expected to improve the team’s abilities, while keeping the pilot out of harm’s way, but still in control.