SOURCE: ET

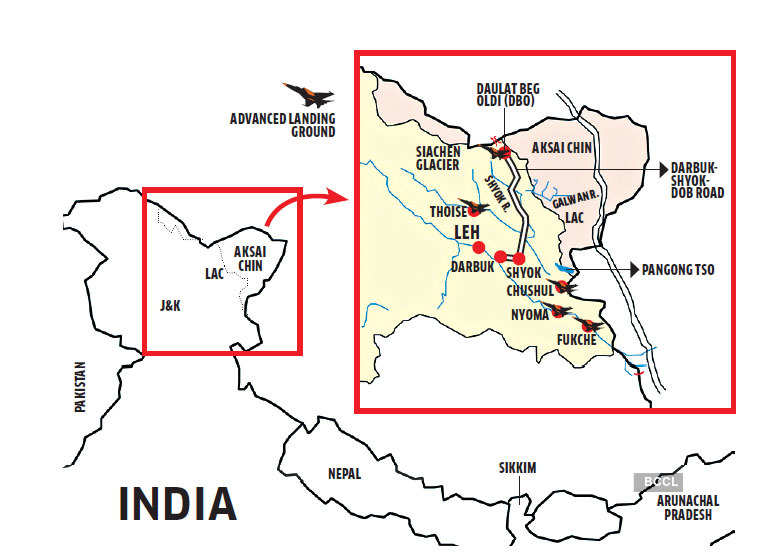

Since early last month, the Chinese troops have moved inside the Indian territory in Ladakh, the flashpoint being Pangong Tso in the east, and the Galwan Valley that overlooks the newly built and highly strategic road from Darbuk to Shyok to Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO). In the cold desert, DBO plays a critical role: it’s next to the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Aksai Chin as well as the historic Karakoram Pass.

Located at an altitude of 16,614 ft, DBO houses the world’s highest airstrip — also called advanced landing ground — which remained non-operational between 1965 and 2008. In May 2008, the airstrip was reactivated when former vice-chief of air staff, Air Marshal (retd) Pranab Kumar Barbora, who was then the Western Air Command chief, landed an AN-32 aircraft there. The entire mission was secret: there was no written order and even the then defence minister AK Antony was kept in the dark. Edited excerpts from an interview with Shantanu Nandan Sharma:

Daulat Beg Oldi airstrip was reactivated after 43 years when you flew an AN-32 transporter in May 2008. Would you share some details on why and how that decision was taken?

It all started in 2008 when I joined as the commander-in-chief of Western Air Command, the jurisdiction of which spread from Ladakh to the deserts of Rajasthan. There were about 60 Air Force stations under me. When we analysed how the Indian Air Force could maximise its logistics support to our Army and paramilitary personnel stationed in that difficult terrain near the LAC, Daulat Beg Oldi cropped up.

We had made plans for Ladakh’s other advance landing grounds, too — for example, Thoise, Chushul and Fukche. But Daulat Beg Oldi stood out for various reasons. First, it’s the highest landing ground in the world. Second, it’s just a few kilometres away from the Karakoram Pass. The airstrip was built in 1962 to check the Chinese as well as to stonewall any incursion from Pakistan from the glacier’s side.

But the landing ground had to be abandoned in 1965. We continued to send helicopters there to drop materials though it was beyond helicopters’ safety margins.

Why was the landing ground abandoned in 1965?

After the 1962 war, army engineers did a fantastic job in building this landing ground, but a decision was taken not to fly any two-engine aircraft to that height. After all, during the take-off, if one engine fails, all are dead. At that time, Packet was the only aircraft that was found suitable to fly to Daulat Beg Oldi, as the two-engine aircraft was modified in India by adding one more small engine. So, it was practically a three-engine aircraft. But Packet was written off in 1965 after the aircraft had gone through its life cycle, so the airstrip also became unused. The area remains hostile. There is less oxygen, there is no vegetation there. The personnel had to walk for days to reach the outpost.

But why was no attempt made in 43 years to reactivate Daulat Beg Oldi even as threats from China remained a constant?

At least five attempts were made. When I wanted to reopen the airstrip, I spotted five files. But after examining those, I realised that if I created another file and put up my request in writing, I won’t get a go-ahead. All the earlier files had ended with a ‘No’ for various reasons.

So, I decided to reactivate Daulat Beg Oldi airstrip without any written permission. I decided, let’s not create any file, let nothing be in writing. After all, if you ask for permission, all the old files will be called, and the result will be another ‘No’. Instead, I talked to my counterparts in the Army and select Air Force officers to get a quick study done on the condition of the airstrip and other preparations.

After all, it was not used for 43 years. Soon, I received a report — again all verbal — confirming that there was no major crack on the ground. For our part, we had to take care of a few air elements, as AN-32 is not supposed to land above 14,000 feet. More than the landing, what was problematic was the take-off. What if one engine switched off? We undertook special trainings, albeit quietly, to enhance our safety norm. We weighed in various scenarios: like, what if a tyre needed to be changed without switching off the engines?

Finally, when we came closer to the date of flying — May 31, 2008 — I spoke to the then chief of air staff (Air Chief Marshal Fali Homi Major) and army chief (General Deepak Kapoor) in Delhi’s Air Force golf course and took their verbal permission. I also briefed the then vicechief of air staff, Pradeep Naik. The defence minister (AK Antony) knew only after we had accomplished the mission.

What happened on the D-day?

We had five people in the aircraft — two Air Force pilots, one navigator, a gunner and I — as we flew the AN-32 from Chandigarh. We landed at Daulat Beg Oldi just before 9 in the morning. We kept the entire operation a secret.

My wife somehow got an inkling, but the spouses of other crew did not know anything about the mission. We spent some time on the top; while returning, one of the senior army officers accompanied us. When we took off from Daulat Beg Oldi, it was like a bumpy camel ride on an unpaved ground. But we successfully lifted the aircraft and landed in Thoise before flying back to Chandigarh. There was a standby aircraft flying around to monitor our plane. We immediately transmitted to Delhi — yes, we have reactivated Daulat Beg Oldi.

We broke the ice and proved a point that we were capable. We surprised the Chinese. Later, in 2013, a four-engine aircraft C-130 Hercules landed there. Look, it’s 2020 now, not 1962.

https://defencenewsofindia.com/i-decided-to-reactivate-daulat-beg-oldi-airstrip-without-any-written-permission-air-marshal-retd-pranab-kumar-barbora/