SOURCE: INDIA TODAY

On April 1 this year, the diplomatic lines between New Delhi and Beijing were clogged with messages of peace and friendship. Exactly 70 years ago, India had done what seemed unthinkable for a non-socialist bloc country at the time, it recognised the government of the Communist Party of China which had only the previous year overthrown the Chinese Nationalist Party.

In his letter to Chinese President Xi Jinping in April, President Ram Nath Kovind observed how the two sides had “made considerable progress especially in the last few years in enhancing our bilateral engagements in a number of areas, including political, economic and people-to-people ties”. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in his message to Chinese premier Li Keqiang, referred to the two countries as two ancient civilisations with a long history of mutually beneficial exchanges over centuries and looked at taking the development partnership to greater heights.

If it had not been for the coronavirus pandemic, which spilled out of Wuhan and infected the world, leading to a nationwide lockdown in India, there would have been a series of events to celebrate the anniversary.Indian generals were secretly delighted at how the ‘Wuhan Spirit’, the informal summits between President Xi and Prime Minister Modi (named for the site of their first informal summit in 2018), had bought them time to focus on Pakistan and the infrastructure of terrorism. It was quite likely this heady spirit that masked the intent and concealed the dust clouds of the two People’s Liberation Army (PLA) motorised divisions moving towards the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Eastern Ladakh in late April.

Multiple clashes broke out in early May all along the 3,448 km-long LAC, mainly along the 840 km stretch in Eastern Ladakh. The PLA and the Indian Army are now facing off in a way they haven’t since the last time they had a border skirmish in 1967. There are unlikely to be any celebrations this year and the prospect of a third Modi-Xi informal summit, which would have been held in China this year, has all but vanished. Talks between the two armies, on for over two months, have made little headway and the PLA seems intent on expanding the territory it controls along the disputed border. As a result, the favourable view Indians held of our relations with China has dropped drastically.

Seen from New Delhi’s perspective, the strategic threat now posed by an increasingly assertive China could not have come at a more inopportune time. The post-Independence Indian state has rarely been gripped by a three-pronged crisis like it is now, a public health crisis, an economic downturn caused by one of the world’s harshest lockdowns and a military threat on its borders. These crises have constricted India’s options at gradually reducing its dependence on its giant northern neighbour, also its largest trading partner.

Among the darkest assessments of what New Delhi faces is of an assertive Xi Jinping, who has seized the opportunity to move in on all of China’s neighbours. The rising China was summed up by exiled Chinese artist Ai Weiwei in a June 14 interview to The Indian Express: “China is a Transformer-like country the West cannot fully imagine. It employs a state capitalist system with communist tactics. It is multifunctional, impossible to describe and cannot be measured with the same standards. At the same time, it is under the most restricted control and driven by a clear vision and purpose.” The interview, ironically, appeared just a day before the PLA ambushed Indian army soldiers in the Galwan Valley killing one officer and 19 soldiers. The fightback by the Indian Army saw an unknown number of Chinese soldiers on the ground killed. The incident, a watershed in ties between the two countries, may have reminded policymakers that the PLA is essentially the army of the Communist Party of China.

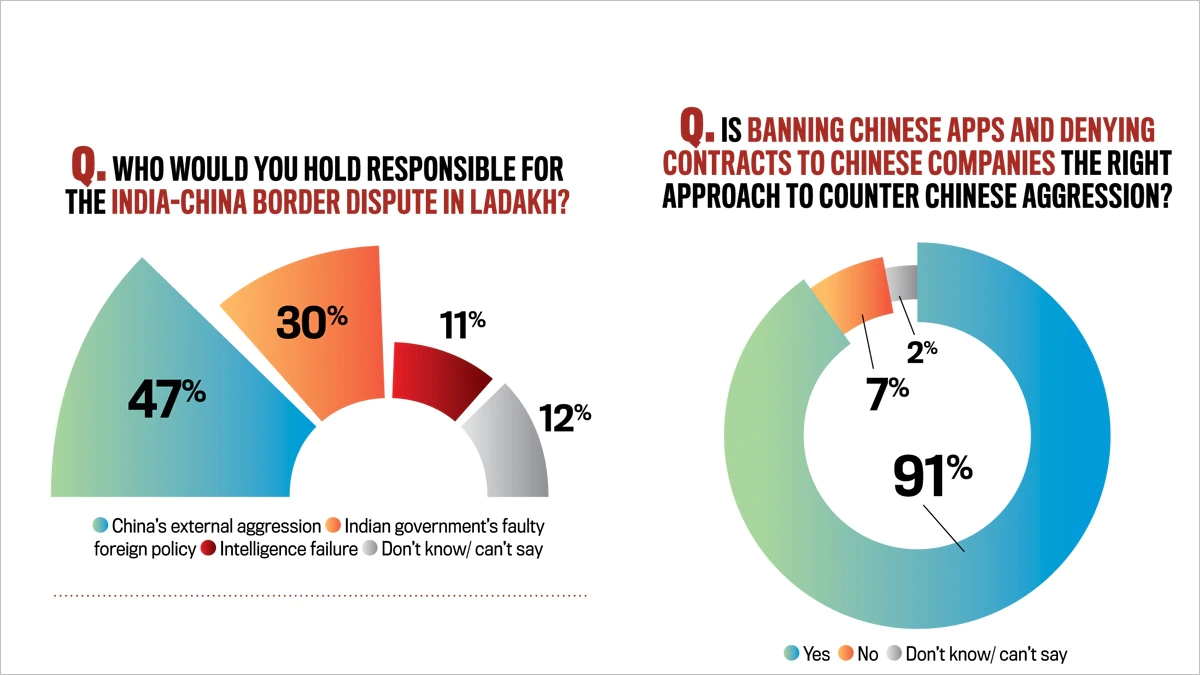

In the period since our last Mood of the Nation (MOTN) poll, we have undertaken a journey, travelling from the Wuhan Spirit to the Ladakh Loathing. In January 2020, 38 per cent of respondents thought relations between India and China had improved over the past five years. This month, an overwhelming 84 per cent of MOTN respondents believed Xi Jinping has betrayed Modi. Ninety one per cent believe that the government’s banning of Chinese apps and denying contracts to Chinese companies was the right approach to countering Chinese aggression; and 67 per cent say they are ready to pay more for goods not made in China. The distrust of China has never been this high. Even in the first MOTN, after the 72-day Doklam stand-off between India and China in 2017, 42 per cent of the respondents in the January 2018 poll believed that relations with China had improved.

Forty-seven per cent of people now hold China’s external aggression as responsible for the India-China border dispute in Ladakh. But, interestingly, 41 per cent also believe it is the government’s fault, 30 per cent held India’s faulty foreign policy as responsible for the dispute, while 11 per cent believed intelligence failure to be the reason.

A majority, 59 per cent, believe we should go to war with China, while 34 per cent say we should not. Seventy-two per cent believe India can actually win against China with only 19 per cent believing we can’t or that ‘it will end in a stalemate’.

War, however, limited in scope or scale, is clearly not in anyone’s interest. The fact that it is even being considered as an option by the public shows the level of anger Indians have towards China and the extent of Beijing’s strategic miscalculation. The government is currently in the process of recalibrating its China policy. This shift, the biggest in decades, is likely to take several factors into account, like the fact that President Xi will be around for a long time, or that India now has many more options than it did in the past, for example, reaching out to like-minded Asian democracies similarly troubled by a belligerent China. It has to shun the temptation to play to the gallery and look at the long road ahead.