Strategic prudence calls for India’s security planners to ensure that India never faces full-scale war on multiple fronts

By Vikas Gupta

Defence News of India, 1st March 24

With the Lok Sabha elections around the corner, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) launched a fortnight-long drive on Monday to gather suggestions for its election manifesto. Seldom short of organizational resources, the party has sent out video raths (chariots) to crowd-source suggestions from numerous assembly constituencies. The party has also invited suggestions through the NaMo App, placed 6,000 suggestion boxes across the country and mobilized its cadres for face-to-face meetings with potential voters. By March 15, the BJP plans to obtain inputs from ten million Indians for its 2024 general elections manifesto — called the “Sankalp Patra” or Letter of Resolution. From these, the party will be distilled the defence and security-related issues that will feature in the BJP’s manifesto for 2024.

In its 2014 and 2019 manifestos, the BJP had raised four major and several minor issues relating to defence. First, the manifesto accused the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government of being sloppy on security, leading to multiple border intrusions by China and Pakistan, a shortage of combat aircraft, warships and submarines, multiple accidents involving naval warships, growing pressure from “Pakistan backed terror groups” and illegal immigration from Bangladesh. While these issues are inflammatory, they are not new.

Second, the BJP manifesto pledged to “update” India’s nuclear doctrine. This triggered speculation that New Delhi was considering abandoning its long-held “No First Use” policy. The 2014 manifesto pledged to “Study in detail India’s nuclear doctrine, and revise and update it, to make it relevant to challenges of current times.” It is unclear whether this meant a larger nuclear deterrent, or the creation of an arsenal of tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs) that would counter Pakistan’s much-hyped TNW weapons. Eventually nothing came of this.

Third, the BJP’s 2014 manifesto promised to restructure higher defence management, putting aside the fact that the NDA had itself shied away from appointing a tri-service chief of defence staff (CDS) whilst in power. In that manifesto, the BJP promised to “ensure greater participation of Armed Forces in the decision-making process of the Ministry of Defence (MoD).” This would integrate the ministry with the military and create structures where uniformed soldiers worked alongside bureaucrats, even as their bosses. A Group of Ministers (GoM) had proposed this measure in 2001, but the BJP encountered strong opposition from bureaucrats, eventually leading to the creation of a halfway house — the Integrated Defence Staff (IDS) — where the three services worked together while the civilian bureaucracy remained aloof. The UPA had gone along with this tokenism for its entire decade in power.

Finally, the BJP’s 2014 manifesto mentioned a range of minor pledges, such as recruiting higher-calibre officers to overcome a debilitating, 25 per cent shortfall (not yet achieved). It pledged to build a national war memorial (achieved), The growing political clout of ex-servicemen was evident in the BJP’s promise to appoint a “veterans’ commission” for addressing problems of retired soldiers, sailors, airmen and their families. The BJP vowed to implement the policy of “one rank, one pension” (largely achieved). Promising to boost indigenous defence production, the BJP said it would “encourage private sector participation and investment, including FDI (foreign direct investment) in selected defence industries.”

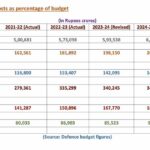

Neither the BJP, nor the Congress before it, made any manifesto commitments on defence spending, even though allocations have plummeted from 4 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the late 1980s to less than 2 per cent today. All 31 member countries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) are required to spend 2 per cent of their GDPs on defence even though, as military allies, collective defence is assured.Article 5 of the Treaty provides that every member will consider an act of violence against one member as an armed attack against all members and will take the actions it deems necessary to assist the ally attacked. With India choosing to stand alone in the face of an enemy attack, there have been calls for real defence allocations to be pegged at 3 per cent of GDP. However, with real defence allocations falling year after year, a 3 per cent defence spending pledge is unlikely.

This parsimony is also evident while setting growth targets in the aerospace and defence industry. Here, political parties have chosen to promulgate growth targets through policy documents rather than political manifestos. Over the last two decades, growth in indigenous defence production has been based on a 2018 MoD roadmap titled the Defence Production Policy of 2018, or DPrP 2018. This set out an annual target of Rs 1.7 trillion (then $26 billion) in aerospace and defence services and production turnover by 2025. This was to through additional investment of nearly Rs 70,000 crores (then $ 10 billion), creating employment for nearly 2 to 3 million people. The 2018 policy also targeted exports of defence goods and services worth Rs 35,000 crores (then $5 billion) by 2025.

When a production target needed to be revised upwards, as was the case with industrial production last week, the impending 2024 manifesto was not chosen as the medium to do so. Instead, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh announced that aerospace and defence services and production would touch Rs 3,00,000 crore (US $36 billion) in by 2028-29. Additionally, he said their export production would be raised in the same time-frame to Rs 50,000 crore ($6.25 billion).

In order to absorb the higher volumes of manufactured goods and services, the 2024 manifesto must include a coherent policy to increase their export. From an arms importer, India has found a place in the list of top-25 arms-exporting nations. Seven-eight years ago, defence exports were below Rs 1,000 crore. Today, they have has touched Rs 16,000 crore.

The BJP’s 2024 manifesto would also do well to explain how the government planned to execute platitudes such as “a two-front war”– which involves militarily defeating Pakistan, holding off China, dealing with insurgents in Jammu & Kashmir, while also ensuring that we remain masters of the Indian Ocean. On the face of it, having to fight a two-front war would represent the simultaneous and comprehensive failure of Indian strategy, diplomacy, border and military management and our internal security. Structuring our security for a worst-case scenario would warp our defence planning, financial allocations and troop deployment. Strategic prudence calls for the country’s top security planners to collectively ensure that India is never reduced to a position where it faces full-scale war on multiple fronts.