Agnipath pits teammates against each other, creating incentives for failure rather than each other’s success

By Vikas Gupta

Company Standard, July 1, 22

The government, deaf to protests, is moving forward with the implementation of the so-called Agnipathe Yojana recruitment program which he announced without warning on June 14. Without much explanation of its pros and cons, the Ministry of Defense (MoD) has touted it as a “transformative measure” that will alter the recruitment pattern of Mohawks’ (hereinafter, soldiers, sailors and airmen who enlist under the Agnipathe Yojana) the current 15-year seniority obligation which ends in a lifetime pension; to a mostly short-term contract under which annual tranches of recruits will serve for four years. After that, 75% of them return home without a pension. This has sparked deep anger among unemployed youths, who have already missed more than 100,000 military recruiting vacancies in two years of lockdown, and will miss more until recruiting resumes.

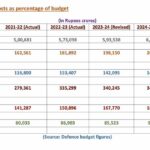

Pensions have become, especially after the implementation of “One Rank, One Pension” in 2015, an unaffordable part of the annual defense budget. In the current year (financial year 2022-23) defense allocation of Rs 525,120 crore, a whopping 23% – around Rs 119,696 crore – is allocated to pensions. Add to this the payroll of serving soldiers, sailors, airmen and civilians (hereafter “soldiers”), and personnel costs amount to 54% of the total defense budget.

The objective of the Agnipathe Yojana is clearly to reduce pension liabilities. From each annual batch of recruits - 46,000 recruits in each of the first four years, 90,000 in the fifth year; and 125,000 from the sixth year – a quarter will be chosen to be kept in service. This means that from the 10e from the year, Agnipath will produce 31,250 soldiers each year (25% of 125,000) for extended terms of service, while another 93,750 will return home after completing their four-year terms of service.

The Ministry of Defense has decided that the candidates selected Mohawk shall be drafted into the army, navy and air force under their respective service laws for a period of four years. They will form a separate rank in the army, different from all other existing ranks. After four years of service, Mohawk will be offered the opportunity to apply for permanent enlistment in the military. The selection will be the exclusive competence of the Armed Forces. Entry will be on an “All India, All Class” basis and the eligible age will be between 17 years and six months to 21 years.

The Department of Defense says there will be a range of benefits to Agnipath. He says the basis would beto be younger, fitter, more mentally robust and more technologically savvy, with the the average age is now 32 years old at 27 years old. These young soldiers, according to the Ministry of Defense, would provide a bank of disciplined employees, who could easily escape government and factory jobs. To facilitate this transition, the government has reserved jobs for retirees Mohawks, including 10% vacancies in the Central Armed Police Force (CAPF), the Coast Guard, in civilian positions in the Ministry of Defense and in 16 public sector defense companies. Some 85 private companies have promised jobs to retirees Agniviers. To facilitate his transition to civilian life, the Ministry of Defense will grant each Agnitate a “Seva Nidhi” package at the end of the four-year engagement, amounting to Rs 11-12 lakhs tax-free. Even so, the by Agniveer his remuneration, which starts at Rs 30,000 per month and rises over three years to Rs 40,000 per month, ensures that he (women are not yet covered by this scheme) remains at a lower level of remuneration than even the most junior soldier in the unit.

In addition to the financial implications, the Agnipath Yojana should not be implemented at the expense of a unit’s combat effectiveness. For an army like India’s, which is operationally engaged year-round on two and a half fronts - China, Pakistan and Jammu and Kashmir - treating soldiers as equals has always been a article of faith and a basic tenet of combat leadership. If there are two distinct levels of pay for soldiers performing the same duties on the battlefield, it won’t be long before whoever receives the lowest salary turns to their highest-paid compatriot. He will reason - and, sooner or later, express his belief - that since the other is better paid, he must take more risks in operations and perform his battlefield duties better as well. This will be the inevitable result of the introduction of differential recruiting and service models within a single combat unit.

The biggest unknown in this risky move is how human relations will play out – not just between the Mohawkwho will compete with their comrades for permanent jobs beyond their four-year terms – but also between the Mohawk and existing full-time soldiers. It should be obvious to military leaders, steeped in the regimental system which is itself based on long-term loyalties - that Agnipath pits teammates against each other, creating incentives for each other’s failure rather than each other’s success. Instead of soldiers functioning as brothers in arms and comrades who risk their lives for each other, the structure of the Agnipathe Yojana encourages compatriots to see each other as competitors, the success of one being at the expense of the other. Everyone knows that out of four classmates, only one will be kept in service and that too under more favorable conditions than before. How this plays out may hold the keys to Agnipath’s success or failure.

All countries that have implemented major military personnel and manpower reforms have done so with great deliberation and an awareness of the high cost of failure. Nowhere are the risks higher than in India, where defense allocations are miniscule, relative to the size of the force. Yet, incredibly, the Agnipathe Yojana was hastily announced without even a small-scale pilot project to validate key assumptions and beliefs. Instead of widely publicizing the proposed draft and holding consultations and discussions, the military rushed headlong into implementation. It’s still not too late to step back and get buy-in from the most important stakeholders – the army’s combat units.