More clarity needs to emerge on specifics of infrastructure creation, patrolling, buffer zones and status quo ante in Eastern Ladakh

By Vikas Gupta

Defence News of India, 01 Nov 24

In May and June 2020, thousands of China’s border guards and soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) emerged from the winter freeze in Tibet and Xinjiang and crossed the Line of Actual Control (LAC) into Eastern Ladakh, capturing Indian territory along five separate axes. From north to south, these axes were: the Depsang plain, Galwan River valley, Gogra – Hot Springs, Pangong Tso and Demchok. Indian Army units and formations in Ladakh were taken by surprise, each having suspended its own patrolling due to the risk of spreading the coronavirus contagion, Covid-19, which had emerged in China the previous year. But that tactical misjudgement left open for the Chinese the doors of Ladakh.

By the time India’s Northern Command could mobilise its reserves and pump troops into Ladakh to block further PLA intrusions, large numbers of Chinese soldiers had taken up positions within Indian territory, their forward defences supported from the rear by artillery and tanks. Indian patrols found the Chinese blocking them with unusual violence. On June 15, 2020, the most egregious of these clashes resulted in the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers and of an indeterminate number of Chinese – marking the first combat fatalities on the Sino-Indian border since 1975. The inevitable Indian counter build-up took its time, given the mammoth logistics involved in airlifting 42-tonne T-90 tanks and artillery guns to support the Indian army’s forward positions where they were, in many cases, eyeball-to-eyeball with the PLA.

These events must be seen in the context of Ladakh’s geography. Some of the untutored press headlines of the day, e.g. “Sino-India confrontation in the Himalaya,” are unaware that the forward Indian posts involved are part of the Karakoram range, not the Himalayas. Similarly, the Chinese troops’ intrusion into Ladakh took place on India’s small part of the Tibetan plateau.

In the four-odd years since the confrontation was sparked off, Beijing and New Delhi have engaged in diplomatic dialogue and, in addition, have held 21 rounds of talks between senior military commanders from both sides. The military-to-military discussions are credited with having negotiated the disengagement, first of troops in the Galwan valley, followed by troops in the Hot Springs – Gogra area and then, in the north bank of the Pangong Lake. However, with Chinese troops continuing to face off against the Indians on the Depsang plain and the Demchok border, the two most important border flashpoints remained unaddressed.

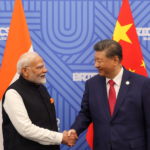

Over the last 10 days of October, India’s Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) has been signalling that Beijing, under consistent Indian pressure, has agreed to implement what it has refused to even discuss so far – that is the mutual disengagement of troops in Depsang and Demchok. If China is accommodating on Depsang and Demchok, a resolution of the broader Sino-India territorial dispute in Eastern Ladakh would be conceivable. India’s Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri announced that intensive diplomatic and military negotiations over the past few weeks had resulted in an agreement on patrolling arrangements along the LAC. This had led to disengagement and a resolution of the issues at stake.

However, the Indian announcement that a Sino-Indian settlement had been reached, encompassing Depsang and Demchok has not been corroborated by officials from China’s Foreign Ministry or Ministry of National Defence.

On Thursday, October 24, a statement from China’s Defence Ministry indicated that further negotiations still remained. Acknowledging that China and India had been able to “reduce differences” and build “some consensus” on disengaging troops to end the standoff, the Chinese said they agreed to maintain dialogue to reach a resolution acceptable to both sides at an “early date”. On Sunday, October 27, Indian foreign minister S Jaishankar told an audience in Mumbai that talks were still at a preliminary stage. “At places where the tension was more, we decided not to patrol it (hic). So, the current agreement will allow us to look at the next step and discuss how to manage the borders. Not everything is resolved but we have reached the first phase,” Mr Jaishankar declared. “We will soon resume patrolling along the LAC in Ladakh”.

Questions that need answers

Comparing the statements and announcements from New Delhi with those from the army in Ladakh, there appears to be a differential in their levels of optimism. It would be prudent to ask certain questions so as to ensure answers are at hand to explain these differences.

First, has the status quo ante of April 2020 actually been fully restored, especially in the flashpoints of Depsang and Demchok? According to the army, disengagement commenced on Tuesday and was completed on Wednesday. Indian Army sources said patrolling in these areas would commence by the end of October 2024, which means that the first Indian patrols should be moving at this moment towards the border in Depsang, unimpeded by the Chinese.

Is that the case? Or does the answer lie in Jaishankar’s admission that talks are still at a preliminary stage. At this crucial moment, where does the truth lie?

Second, Army sources have been quoted as saying there were no changes in the areas where disengagement had taken place earlier and buffer zones established. This clearly means that the buffer zones established at Galwan, Pangong Tso, PP 15 and PP 17A, Gogra and Hot Springs remain in place. How does that square with the simultaneous assertion that the status quo ante of April 2020 had been restored? After all, a significant part of the buffer zones established at Galwan, Hot Springs, Gogra and Pangong Lake were patrolled up to April 2020 by Indian patrols. That status quo ante has clearly been abandoned.

Third, the Chinese government has unapologetically stated that one of the key reasons for the PLA’s intrusions into Eastern Ladakh was India’s infrastructure creation along the LAC, especially strategic roads such as the Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DS DBO) border road, which linked the Pangong Lake area in central Ladakh with the DBO area at the strategically vital northern tip of India – the Karakoram Pass.

The government needs to answer the critical question of whether it has accepted any restrictions on its infrastructure creation activities, or linked them in any way with China’s infrastructure development.

Finally, the government needs to come clean on about patrolling restrictions, if any, that it has accepted in order to avoid face-offs between Indian and Chinese patrols.

[ENDS]