SOURCE: INDIA TODAY

Sometime in late April, two Chinese motorised divisions, over 20,000 soldiers in trucks, equipped with light tanks and self-propelled howitzers, left their exercise area at the edge of the Gobi desert in Hotan, Xinjiang, and hit the ‘Sky Road’. The Xinjiang-Tibet highway is thus called because it is one of the world’s highest motorable roads, with an average altitude of 4,500 metres. From here, these divisions branched off towards a series of feeder roads that took them right up to the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with India.

Once these formations were in position along the 480-km stretch in eastern Ladakh, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of China began Phase 2 of their military plan, triggering incursions across the LAC in four locations using small batches of troops.

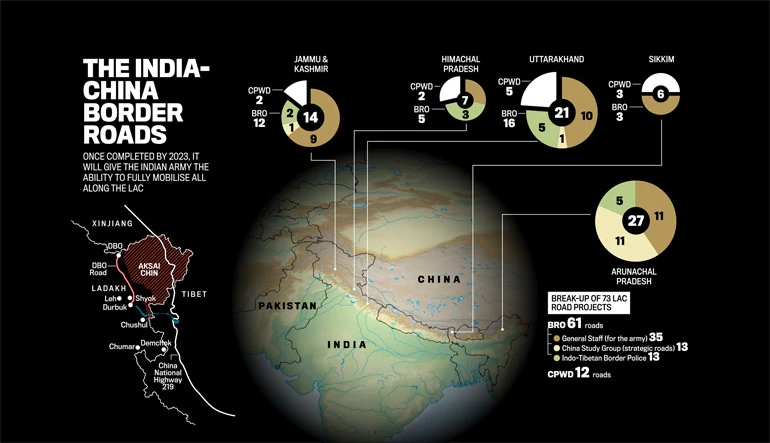

The PLA force was insufficient for a full-fledged invasion (for which they would need between four and six divisions) of Ladakh but just enough to block any attempt at militarily evicting them. The Indian Army rushed two infantry divisions to beef up the Leh-based 3 Division even as the IAF flew in fighter jets and helicopter gunships as deterrents. The counter deployment rode on freshly topped strategic roads and bridges built in the biggest post-Independence burst of infrastructure-building, over 4,700 kilometres, along the disputed frontier.

The largest military standoff between the Asian giants since the 1962 war culminated in a violent clash on June 15 which claimed the lives of 20 Indian soldiers and an unspecified number of their PLA counterparts. A two-hour phone call between National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi on July 5 saw both armies begin the process of stepping back or ‘de-escalating’.

On July 7, just hours after the de-escalation began, defence minister Rajnath Singh asked Lt General Harpal Singh, director-general, Border Roads Organisation (BRO), to expedite the existing projects along the LAC, road infrastructure, 30 permanent bridges and tunnels worth Rs 20,000 crore. The directives to the MoD’s road construction agency was a clear signal from the government—de-escalation did not mean the foot was being taken off the infrastructure pedal. “Our work did not stop through the standoff, we’ve in fact accelerated construction,” says a senior government official. The BRO is also flying in road construction workers from states like Jharkhand to achieve their expedited targets this year. Intense construction over the past decade has brought Indian trucks, battle tanks, infantry combat vehicles, artillery, Brahmos missile trucks and road-mobile Agni ICBM launchers close to the border.

“India’s armed forces have the capability to move into multiple sectors at one go,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi said in his June 19 address at an all-party meeting. India’s infrastructure push, well within its side of the LAC, is a frantic and belated attempt to match the Chinese construction on the plateau. The BRO’s budget was more than doubled—from Rs 5,500 crore in 2017-18 to Rs 11,300 crore in 2020-21.

One of the many reasons analysts have attributed to the PLA’s move is a message to halt the Indian build-up. The most crucial project to have been completed so far, the 260-km Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) road is, as an MoD briefing note calls it, ‘highly sensitive and critical for army formations in the area’. The all-weather road with multiple bridges cuts journey time between Leh and Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO), the northernmost outpost, from a week to three days.

In a June 19 article on news portal warontherocks.com which was widely read by India’s security establishment, Yun Sun, senior fellow and co-director of the East Asia Program at the Stimson Center, argued that the Chinese saw Indian infrastructure development ‘as a consistent and repeated effort by Delhi that “needs to be corrected every few years”’. ‘For the Chinese,’ it goes on to say, ‘the infrastructure arms race in the border region has enabled the repeated incursions and changes to the status quo and therefore needs to be stopped. Otherwise, all the things China fought for in the 1962 war would have been in vain.’

The Infrastructure Race

The India-China border dispute began when the PLA’s takeover of Tibet in 1950 turned the two countries into neighbours for the first time in history. In 1951, Chinese road crews started hacking their way through the desolate Aksai Chin, completing the gravel-topped Xinjian-Tibet highway to link the People’s Republic of China’s two newest acquisitions in 1957. The discovery of the road running through territory claimed by India was one of the triggers for the 1962 border war. India’s ‘Forward Policy’ riposte, sending soldiers to man small pickets on its territorial claims, was doomed among several other things by the utter lack of border infrastructure in the Himalayas. Mules, transport aircraft and helicopters could not substitute non-existent roads. The military post in the now infamous Galwan Valley, for instance, one of dozens set up before the war, had to be supplied by transport aircraft before it was overrun by the PLA in October 1962. After the war, the borders lay largely undisturbed and lightly patrolled for nearly three decades. Infrastructure was given a miss, deliberately, as it would emerge in a 2013 statement made by then defence minister A.K. Antony in the Lok Sabha. “Independent India (for) many years had a policy, the best defence is not to develop the border.”

The more recent awareness on the need for connectivity along the disputed boundaries came, not from the China border, but from the opposite side. A key part of General Pervez Musharraf’s Operation ‘Koh-Paima (Call of the Mountains)’ in 1999 saw the Pakistan army dragging howitzers atop mountaintops near Kargil to shell and cut off the Srinagar-Leh highway that supplied the Indian army’s garrison in Siachen. The Indian army forced the Pakistan army to roll back in the Kargil War. Shortly after the conflict, the cabinet committee on security in 1999 approved the speedy construction of 13 border roads.

This was around the time that a rising China’s economic muscle began manifesting along India’s LAC. By 2006, a latticework of 36,000 miles of black-topped roads swathed the Tibetan plateau. The crown jewel was the 1,956-km-long Tibet-Qinghai railway line with foundation pillars sunk into permafrost and coaches pressurised to acclimatise passengers when they arrived. The implication to Indian military planners was clear, the PLA could now bring in 30 divisions, tanks and artillery into the Tibetan theatre in days as opposed to months. The railway marked the start of a policy of transgressions by the PLA along the border which began in 2006 and continued for several years, culminating in May 2020 as a larger military game plan to alter the LAC.

In her 2018 MIT doctoral thesis, ‘Calculating Bully: Explaining Chinese Coercion’, the scholar Ketian Zhang holds the 2006 completion of the railway as ‘the most important factor contributing to increased Chinese transgressions’. China’s infrastructure in the border regions had dramatically improved to the extent that many roads could reach areas merely five or 10 kilometres from the LAC which makes it easier for border forces to patrol along the area, Lin Minwang, a former diplomat at the Chinese embassy in New Delhi, was quoted as saying in the thesis.

The UPA government signed off on the border infrastructure boost in 2006 with its ‘China Study Group’ headed by the NSA, setting ambitious targets to complete 61 Indo-China Border Roads (ICBRs) across the various Indian states facing the LAC by 2012 (see graphic). The BRO, however, was unable to deliver.

A CAG report tabled in Parliament in 2017 noted that only 15 of the planned 61 roads had been completed. The projects had incurred massive cost overruns, 98 per cent of the Rs 4,644 crore estimate had been swallowed in building just 22 roads. Only seven of 46 roads were complete by March 2016, with the deadline for the remaining ones extended to 2021.

There were various reasons for this, chief among them being the peculiar structure and diffused accountability of the BRO. Created in 1960, it built roads for the military but was under the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH). Its inhouse General Reserve Engineer Force cadre sparred with army engineers who manned the BRO. “An agency created with a unique character lost its uniqueness and envisaged efficiency, it had dual controls, it was under the administrative control of the MoD but the MoRTH released its funds,” says Colonel D.P.K. Pillay (retired), a military analyst with the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA).

Add to that were the natural obstacles of building roads along the world’s highest mountain range. “Building roads in the Himalayas is like building on a heap of loose, sedimentary rock that has faultlines, is earthquake prone and bears the brunt of the monsoons,” says Lt General S. Ravi Shankar, former D-G, BRO.

The heavy winter snowfall constricted road building into a single six-month window between May and October. The Chinese, in sharp contrast, have the natural advantage of building their roads on the plateau that is flat and hence more amenable to construction. Huge shifts had already started taking place within the MoD, army and BRO even as the CAG’s alarming report was tabled in Parliament. The biggest change summed up by an unnamed army officer in a 2016 deposition before the Lok Sabha’s standing committee on defence was “the philosophy of not making roads as near to the border as possible had been changed to ‘we must go as far forward as possible”.

A prescient MoD briefing note to the standing committee that year warned of a long-term infrastructure development plan by both China and Pakistan in the northern areas. ‘These plans will enable these countries to concentrate and move sizeable forces all along the Indian border and will pose a significant threat in the event of any conflict,’ it said.

The changes began in November 2014 with the induction of the technocrat defence minister Manohar Parrikar, who was laser-focused on transforming border infrastructure. The BRO was placed under the MoD in January 2015 and closely integrated with the army and defence ministry.

“The biggest changes in the BRO were the induction of tunnel boring machines, constant review meetings and the delegation of financial powers to speed up decision-making,” says G. Mohan Kumar, then defence secretary.

The BRO began working in mission mode, the D-G reporting to then army chief General D.S. Suhag and defence secretary Kumar. “We worked on transformative change, to institutionalise monthly consultative meetings among all the stakeholders and iron out differences,” says Lt General Suresh Sharma, then D-G, BRO.

A new category of ‘Priority 1’ roads was created on the advice of the Director General Military Operations, the key army Lt General officer responsible for military plans. The DSDBO road was one of them. The road had defied attempts at construction given the tricky terrain, especially the crossing over the Shyok river which overflowed with snowmelt during summers. The BRO, for the first time, used micro-piles—high performance, high capacity foundations around 12 inches in diameter, to build a 430-metre-long bridge across the river. It was completed last year.

The organisation also began tunneling in a major way. A tunnel under construction will reduce travel time from the Indian Army’s 4 Corps headquartered in Tezpur, Assam, to Tawang, a town claimed by China, by at least 10 km and, more importantly, convert a normally snowbound highway into an all-weather road when it is completed next year. The strategic 8.8-km-long Atal tunnel being built for Rs 4,000 crore will shorten the Leh-Manali route by 46 km and will be open to traffic this September.

The 72-day Doklam stand-off between the two armies in 2017 was another major factor that speeded up road construction by the BRO. The stand-off began over a road that the PLA began constructing towards a vital ridge overlooking Indian territory and which the Indian army successfully blocked. By 2018, the BRO had constructed a second road to the disputed valley, converting a mule track into a motorable road and is building a third one to be completed by 2021. New techniques like building a road at five ‘attack points’ were used to hasten completion of the strategic 80-km Ghatiabagarh-Lipulekh road near the Indo-Nepal border, inaugurated by Rajnath Singh on May 10.

More importantly, the ICBRs were brought under a five-year works plan, where the BRO would prepare estimates without waiting for specific approvals from the government. The present works plan approved in 2018 is for 282 roads of 22,803 km (including the ICBRs) at a cost of Rs 22,000 crore, and is set to be complete by 2023 which would see India finally catching up with China. The Himalayan race seems poised for an exciting finish.