SOURCE: INDIA TODAY

Seen purely through the lens of national security, the 80,000+ employees of the Ordnance Factory Board (OFB) couldn’t have chosen a worse time to announce a strike. The Indian Army, the OFB’s main customer, is currently deployed along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with China. A strike means the army will have trouble getting urgently-needed equipment, like snow-proof tents, boots, high-altitude clothing and ammunition. This is the very reason the OFB’s 41 factories were set up over the past two centuries, to provide the force with urgently needed materiel in times of conflict, or in this case, a massive standoff with China that looks set to continue as the winter sets in.

The OFB’s unions have announced an indefinite strike beginning October 12 because the Centre is adamant about corporatising the 219-year-old organisation. On May 16, Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman had announced that the government would be doing so to improve the “autonomy, accountability and efficiency [of] ordnance suppliers”.

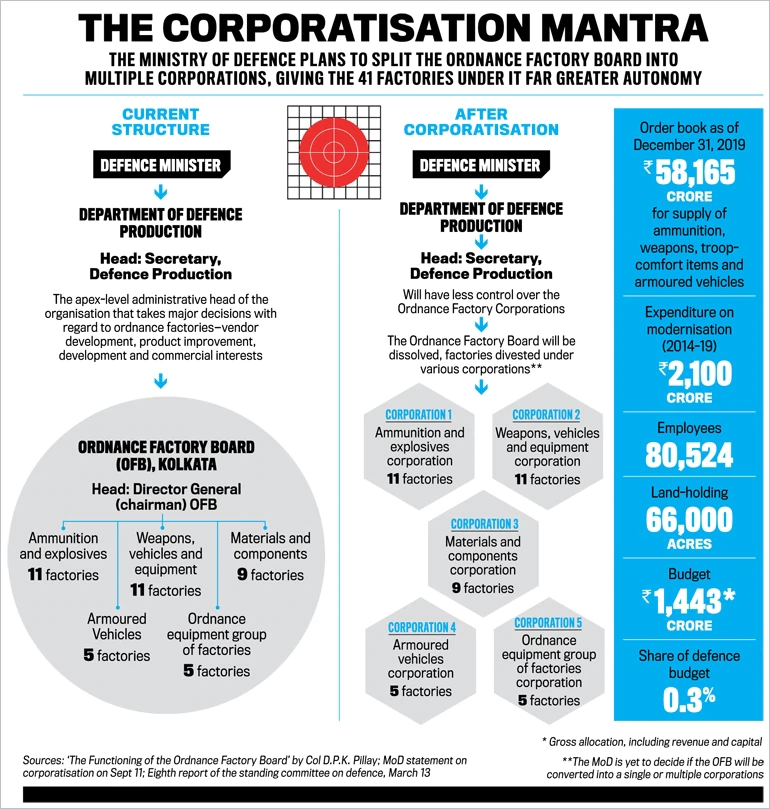

The government plans to break up the monolithic OFB from a single department attached to the defence ministry into several corporations, like the nine existing defence public sector undertakings (DPSUs). On this, matters have proceeded at a breakneck pace over the past four months, with the government appointing a consulting agency, KPMG, to oversee the corporatisation. On September 11, it announced that an empowered group of ministers, headed by Union defence minister Rajnath Singh, would oversee the process. The buzz is that the government plans to announce a decision on the corporatisation before the end of the current financial year.

In the past, OFB unions have often successfully used strikes to keep corporatisation at bay. In August last year, three unions representing over 80 per cent of OFB workers had launched an indefinite strike. A month later, union leaders met with the secretary of defence production, who convinced them to call off the strike, with corporatisation seemingly put on the backburner. That was before the pandemic. OFB officials say that the new announcement by finance minister Sitharaman in May seems to have come from the Prime Minister’s Office, this time around, they worry that corporatisation will go ahead regardless of protests.

AN UNCONQUERED PEAK

Many government-appointed committees have suggested reforming the OFB over the past two decades. “Corporatising the OFB is an unconquered peak,” says Colonel D.P.K. Pillay (retired), a research scholar at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. “There is unionisation and vested interests, their order books are full and their overtime registers are also full, but deliveries to the army are delayed.”

The OFB’s first ordnance factory was the gun and shell factory set up by the East India Company in Cossipore, near Calcutta, in 1801. Its 41st factory is an ordnance factory in Amethi, where a joint venture to produce over 600,000 AK-203 rifles with Russia’s Kalashnikov Concern is being negotiated. Today, the OFB is given about Rs 1,443 crore of support from the defence budget every year, has over 80,000 employees and holds over 60,000 acres of land. More than 80 per cent of the OFB’s current Rs 58,165 crore worth of orders have been placed by the army, though its factories meet barely 50 per cent of the defence force’s requirements. The last major reform was in 1979, when the disparate ordnance factories were brought under a board headquartered in Calcutta. The board is headed by a chairman and has nine members, with five in charge of one cluster of factories making various defence items. The chairman, selected from among the seniormost board members, has an extremely short tenure, of a year or less. The last three chairmen had tenures of six months, 12 months and nine months each.

The factories function as attached offices of the department of defence production (DoDP), itself part of the Union ministry of defence (MoD). Over the years, a deep dissatisfaction has grown within the army over OFB products, an issue central agencies have also highlighted. A 2015 report by the Comptroller and Auditor General noted that 74 per cent of the 170 types of ammunition produced by OFB factories failed to meet the ‘minimum acceptable risk level’, and only 10 per cent met the ‘war wastage requirements’. Another audit, for 2017-18, presented in Parliament in December 2019, noted that ‘the factories had achieved their production targets for only 49 per cent of items. A significant quantity of the army’s demand for some principal ammunition items remained outstanding as on March 31, 2018, thus adversely affecting their operational preparedness.’ The report also noted that OFB exports decreased by 39 per cent in 2017-18 over 2016-17.

“The OFB has a monopoly over several products required by the armed forces,” says Lt General Sanjay Kulkarni, former Director General Infantry and a former member of the Lt General Shekatkar committee (which was set up to recommend reforms in the armed forces). “[It undertakes] minimal innovation, has no incentive to improve quality and cost-efficiency and has no accountability for its products. Corporatisation will put the OFB on par with other DPSUs, managed by its own board of directors with broad guidelines from the government.”

Over the past 20 years, four government committees have made the same recommendation, that the OFB be corporatised to make its factories more efficient. This would mean converting the Ordnance Factory Board into something akin to an Ordnance Factory Corporation, as suggested by the T.K.A. Nair committee in 2000. In 2006, the Vijay Kelkar committee recommended the same, suggesting the corporation be accorded the status of a Nav Ratna, along the lines of BSNL. In 2015, the Vice Admiral Raman Puri committee also recommended corporatising the OFB, as well as splitting it into segments specialising in distinct areas, like weapons, ammunition and combat vehicles. In 2016, these recommendations were reiterated by the Lt General Shekatkar committee.

The trouble, MoD officials say, is a result of the peculiar organisational structure of the OFB. First, since these factories function as attached offices of the DoDP, every decision relating to them, from modernising plant and machinery to entering into joint ventures with other companies, is subject to government regulations and instructions. This reduces their leverage and flexibility. Second, being government departments, they cannot retain profits and, therefore, have no incentive operate cost-effectively. Third, in its present form, the OFB lacks technical and managerial flexibility and hence is incapable of competing with the private sector.

The MoD also says that the OFB monopoly, where it supplies products to a captive customer, the armed forces, brings its own set of problems. The main consequence of this monopoly is that there is no incentive for the OFB to improve quality. This also results in high overhead charges being loaded onto OFB products, with minimal innovation and technology development taking place. There are also issues of low productivity, further compounded by the fact that there is no penalty for delayed delivery to customers.

Lt General P. Ravi Shankar, former Director General Artillery, narrates a story of how faulty mechanical fuses produced by the OFB were resulting in artillery barrels bursting. The issue was identified as one resulting from faulty fuses through an elaborate process lasting several years, he says. The army could potentially have lost 800 guns, nearly a third of its artillery. “The issue of ammunition accidents is a matter of record. Such cases are not limited to one kind of ammunition, it extends to all kinds of OFB ammo, air defence, tank and artillery. We have not had as many losses due to enemy action as we have had due to negligence and poor quality of OFB products,” says Lt General Shankar. An internal army report to the MoD, excerpts of which have been accessed by india today, calculates a loss of Rs 960 crore to the exchequer due to poor quality OFB ammunition. This figure, the report notes, could have bought 100 155-medium artillery guns. What is alarming, though, are the 403 accidents related to faulty ammunition since 2014. Worryingly, the report notes that 27 troops and others have been killed in faulty ammunition accidents since 2014, with 159 suffering serious injuries, including permanent disabilities and loss of limbs. Responding to the report, a senior OFB official termed accidents a ‘complex phenomenon’ involving gun drills and design changes, not only ammunition. “There have been more than 100 accidents between 2011 and 2018 involving ammunition that is not ours,” he said.

However, there is reason to believe that the cure may be worse than the disease. Government-owned corporations have historically not had good operational records. “The government’s history of corporatisation is bleak and in fact has only made matters worse,” says Rahul Chaudhry, chair of the FICCI Homeland Security Committee. He uses the example of BSNL, which was spun out of the department of telecommunications as a public sector undertaking, and is currently saddled with losses of over Rs 39,000 crore. However, in sharp contrast are two major success stories—the Atomic Energy Commission and ISRO, both commissions that are wholly run by the government, and hence closer in character to a government department like the OFB.

OFB officials blame the structure of their organisation for the inefficiency. They say the factories were created only to execute production orders given to them by the MoD on a ‘nomination basis’, that is, without any competition. The organisation also incurs a huge salary bill of Rs 7,000 crore each year to pay over 80,000 employees. “A government department can survive on low margins, but a corporate cannot. Even if we get the freedom to hire and fire, we will still have to deal with unions and we will still be under the MoD”, says the general manager of one of the ordnance factories. The challenge, OFB officials say, is to first make the ordnance factories ‘budget neutral’ (self-sufficient) before they are corporatised. “Otherwise the corporation will be bankrupt on day one,” says a former OFB chairperson who did not want to be named.

While the government debates the commercial considerations, one of the compelling reasons for the OFB’s existence is ‘surge capacity’, wherein idle factories can ramp up production to cater for emergency requirements, whether in ammunition or clothing. OFB officials offer the example of the Covid-19 crisis, where 19 factories worked through the lockdown to produce PPE kits and sanitiser liquid.

“The OFB is a war reserve and not a commercial enterprise,” says C. Srikumar, general secretary of the All India Defence Employees’ Federation, one of the three employees’ federations planning to go on strike. “If we are turned into a corporation, we will become a sick enterprise like BSNL and will be put up for sale.” With the government squarely focused on breaking up the giant that is OFB and increasing the number of state-owned PSUs, that seems to be a business risk it is willing to take.