SOURCE: INDIA TODAY

Up until last week, it appeared that the military standoff between India and China in eastern Ladakh was settling into an uneventful deep freeze as winter approached. Nearly a dozen rounds of talks between both sides had failed to resolve a deadlock, mainly because the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of China refused to pull back its troops to their positions before April 2020. The deadlock was acute along the north bank of the Pangong Tso where the PLA had moved forward by nearly eight kilometres to a point known as Finger 4.

Then, on the night of August 30, the situation changed dramatically. The Indian Army, accompanied by special forces, occupied five key features along a ridgeline south of the Pangong lake, Helmet, Kala Top, Camel’s Back, Gurung Hill and Requin La.

These five strategic features are in an area India considers to be within its perception of the LAC (Line of Actual Control). An Indian Army statement on August 31 said that they had ‘thwarted Chinese intentions to alter the ground situation’. ‘The Chinese had violated the previous consensus arrived at during military and diplomatic engagements in the ongoing standoff in eastern Ladakh and carried out provocative military movements to change the status quo,’ army spokesperson Col. Aman Anand said in a release. ‘Indian troops had pre-empted PLA activity and undertaken measures to strengthen our positions and thwart Chinese intentions to unilaterally change facts on the ground.’ The army has an official word for this, quid pro quo or QPQ, defined as an action to grab territory in exchange for a settlement. It is still unclear whether this was such an operation, but there has been a shift in the ground position. India now holds some cards on the table.

Sources speak of an ‘H-hour’ order on August 28 following which a large number of mountain-trained Indian Special Forces (SF) drawn from multiple units began scaling the heights to occupy vantage points all along the 840-km LAC to thwart the PLA. The Indian move drew a flurry of protests from the Chinese embassy in New Delhi, the PLA and the foreign ministry in Beijing, all of whom accused India of having “trespassed” the LAC. It is currently a hair-trigger situation with troops facing off at the heights and India vigilant on any attempts to alter the status quo in other sectors along the LAC.

“A bold decision has been taken at Chushul at the political level. We have occupied a front along the LAC, and we surprised the Chinese. But there is heightened nationalistic fervour there too. We have to be prepared, rather than gloat,” says Lt. Gen. Rakesh Sharma, former GoC of the Leh-based 14 Corps.

THE TIBETAN ARMY

On August 31, just hours after the Indian Army’s press statement, the Tibetan community in the Union territory buzzed with WhatsApp messages. The messages in English and Tibetan said that Nyima Tenzing, 51, of the ‘7 Vikas’ battalion had been killed in a landmine blast in which another Tibetan jawan was seriously injured. Tenzing’s body was driven home to his house in the Sonamling Tibetan Refugee settlement in Leh, Ladakh, escorted by a Special Frontier Force (SFF) truck and handed over to his family.

But for the tragic death of this Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO), an extremely significant fact would have escaped the theatre of operations. For the first time in recent years, India had deployed its secret Tibetan paramilitary force along the LAC with China. In Ladakh, the SFF acted in concert with the army to occupy the three features on the ridgeline. Among these units was the Chushul-based 7 Vikas.

“China’s position is very clear. We oppose any country, and of course that includes India, which provides any facilitation or venue to forces advocating Tibetan independence,” Chinese ministry of foreign affairs (MoFA) spokesperson Hua Chunying said on September 2, responding to a question on the SFF. The Tibetan force deployments in the Ladakh theatre, in fact, began soon after the Chinese incursions in May this year. The Indian Army pulled out its special forces units trained in high-altitude warfare to hack trails and set up posts along hilltops and ridgelines to observe PLA positions. They were joined in these reconnaissance tasks by an unspecified number of Vikas battalions that surged forward to man key positions along the LAC.

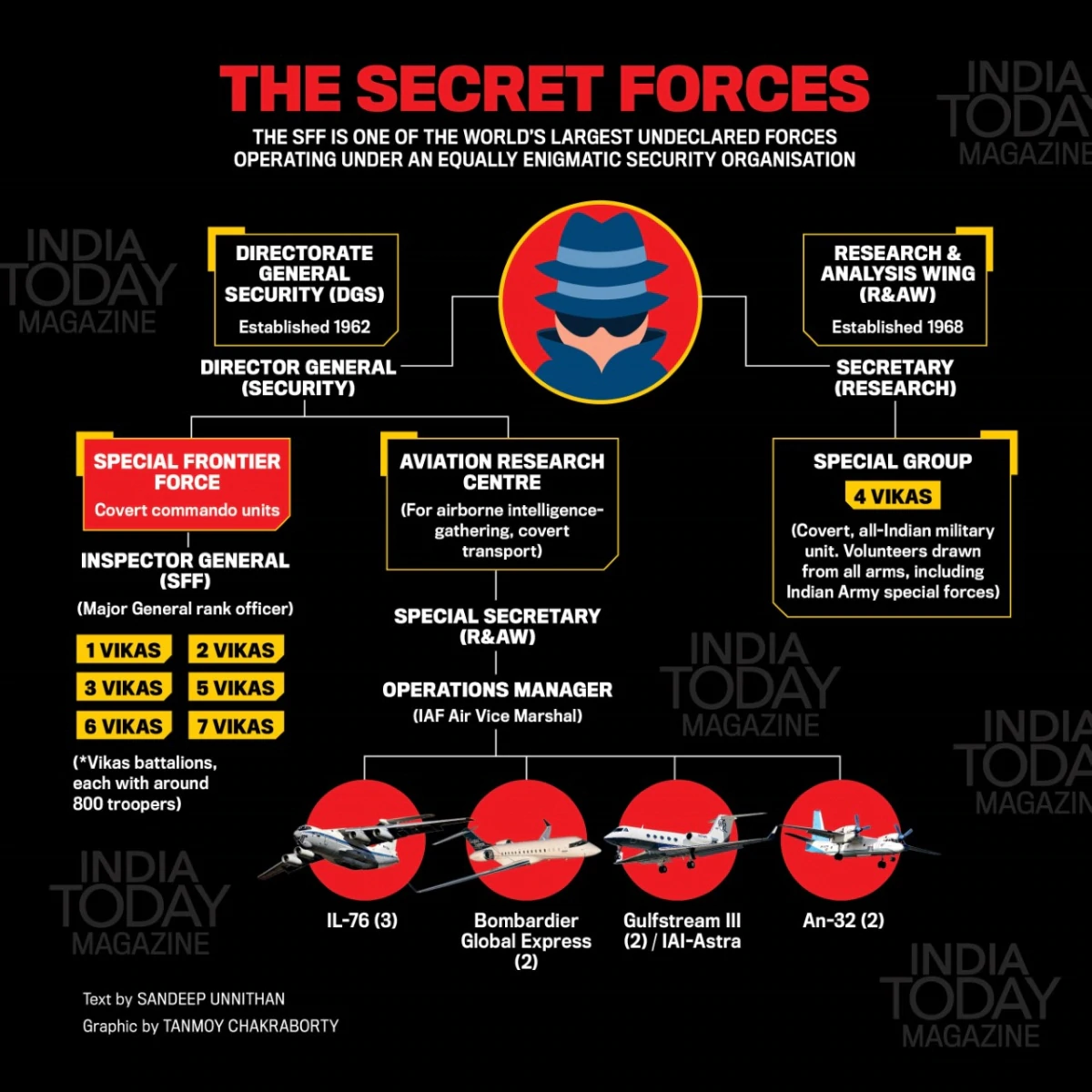

Vikas battalions numbered one through seven are a thinly-disguised alias for the SFF, an enigmatic paramilitary unit manned by ethnic Tibetans, operating under an Indian covert organisation called the Directorate General of Security (DGS). The DGS and SFF were set up in 1962 in the closing stages of the border war with China to fight a guerrilla war inside the Tibetan Autonomous Region.

Given the extreme geopolitical sensitivity of an armed Tibetan volunteer force on Indian soil, the SFF’s existence has never been acknowledged by the Indian government. Indian Army veterans from the unit declined to speak on record, citing a secrecy bond they sign at the start of their deputation.

“The decision to announce that they (the SFF) took part in fighting the Chinese is important,” says Jaideva Ranade, former additional secretary, R&AW (Research and Analysis Wing) “If properly disseminated, it will have the effect of encouraging Tibetans inside Tibet and China. It will worry the Chinese leadership about the likely impact of such news on the Tibetans and whether they will engage in demonstrations or acts of violence.”

The SFF draws its volunteer recruits from a 150,000-strong ethnic Tibetan diaspora, settled mostly in India. Officered by the Indian Army, it has six battalions with nearly 5,000 troopers (equal to around two army brigades). Accounts of its creation are anecdotal as no official records have been published. In 1962, then Intelligence Bureau chief B.N. Mullick swiftly cobbled together the SFF from elements of the Chushi Gangdruk, a Tibetan guerrilla force set up inside Tibet in 1958 to resist the Chinese occupation. The volunteers who fled Tibet entered India and settled in Kalimpong and Darjeeling. The organisation directly reports to the cabinet secretariat under the PMO. It is perhaps no coincidence that the SFF’s raising day, November 14, is then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s birthday, and just a week before the Chinese announced a unilateral ceasefire in 1962.

Training and equipment for the force came from the CIA initially. The CIA had been separately training the Tibetan resistance as far back as the 1950s in guerrilla camps in the US and Nepal. But it was a brief honeymoon, and eventually the SFF became an all-Indian affair under the DGS. The DGS had its own fleet of transport and intelligence gathering aircraft and was headed by the R&AW chief, who wears a second hat as DG (Security). The SFF, also known as ‘Establishment 22’, operates out of Chakrata in Uttarakhand.

Their initial mission, according to Claude Arpi, a Tibetologist who has researched its creation, was to “go back and free Tibet from Chinese occupation six months after the 1962 war”. That moment never came. Over the years, the SFF hardened into a commando force, and a border guarding unit, but were rarely deployed along the border with China. Arpi cites past incidents where SFF troopers reportedly crossed over the border into Tibet on unsanctioned missions, leading to a government decision to keep them away from the border.

The SFF, though, were used in India’s last two wars with Pakistan. Its first inspector general, a maverick Sikh artillery officer named Brigadier Sujan Singh Uban, described the SFF operations in the Chittagong Hill Tracts during the Bangladesh War in his 1985 book, Phantoms of Chittagong. He, however, referred to the unit’s Tibetan origins only in passing. The SFF lost 56 men while 190 troopers were wounded. They were used again during the Kargil war of 1999 when their mountaineering skills came in handy.

Former army chief General Ved Malik mentioned in a tweet how “some of their (SFF) troops, considered expert mountaineers, were employed during the Kargil war on Khalubar (Batalik) and Point 5500 (Sub Sector Haneef).” SFF troopers scaled near-vertical ridgelines in Batalik and Point 5500 to secure ropes for the Indian army soldiers to climb up and capture peaks. It wouldn’t have been difficult for them. SFF troopers are skilled mountain climbers who have to pass a gruelling test at the rock climbing school in Chakrata while paratroopers qualify at the Sarsawa and Charbatia air bases. An Indian Army veteran who operated with them calls them “mountain goats” for their rock climbing abilities and praises their high IQ and language skills. “All SFF troopers speak English, Tibetan, Chinese and the local language of the region they hail from, a trooper from Coorg will speak Kannada and a soldier from Darjeeling Gorkhali,” he says.

Army veterans also say there was a sense of discomfort within the Tibetan government-in-exile about the SFF being used against Pakistan. An Indian Army officer posted with the SFF during the Kargil war says they were withdrawn from the theatre because Tibetan authorities were fearful of an international incident if any of their people were captured by the enemy.

The DGS took care to preserve the SFF’s distinct Tibetan identity. They keep to themselves and rarely mix with Indian Army formations even while deployed near the LoC (Line of Control) or LAC. The battalions have their own regimental flag (a Tibetan Snow Lion), insignia and rank structure, with the Tibetans serving as soldiers and NCOs (non-commissioned officers). A handful of Tibetans were given officer commissions and had risen to the rank of Lt. Colonels by the 1980s, but were subsequently not given officer commissions. All six battalions are now commanded by colonel rank Indian Army officers, with at least five other officers in the unit who are referred to as ‘Indian Army staff’, an indication of the force’s insular nature. The SFF unit also has a female commando company of women, among the first for any military unit in post-Independence India.

The covert unit celebrated its golden jubilee in 2012 without once having seen action on the LAC with Tibet. In fact, it was battling for its very existence; at some point a decade ago, there was speculation that the organisation might be quietly demobilised.

As Arpi points out, there is a dichotomy at the heart of the SFF. The Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of the Tibetan people, is an avowed pacifist. The SFF is anything but. Youngsters who join the unit still dream of a free Tibet which now appears very distant. But from the heights of Ladakh that they currently occupy, they have a bird’s eye view of their homeland.