SOURCE: THE PRINT

At its inaugural meeting on 5 and 6 September 1947, the Pakistan Defence Council, headed by the Prime Minister and minister of defence, Liaquat Ali Khan, outlined both the internal and external functions of the Pakistani army. The first function was to support the civil-political authorities in the tribal region while ensuring that there were no tribal incursions into the hinterland. The second function — external role — was defined in the anachronistic British imperial defence terms: to prevent aggression by a minor power, while preparing to defend against a major power.

In 1947, the Pakistan Army’s war strategists developed a combat doctrine, called The Riposte. It featured a strategy of ‘offensive-defense’. The strategists had served in the victorious British Army of the Second World War. And later, the swagger of the American ethos crept into the doctrine, leading to a concept, which concluded that only an offensive approach could bring victory. A strong offensive was the overriding strategy in 1965 — India was seen as a minor power. Till 1986, ‘offensive’ remained Pakistan Army’s major strategic concept.

The western influence

In the early years of Partition of the sub-continent, the United States pressured India to join the anti-Communist pact as part of the Truman Doctrine, initiated in March 1947 for the purpose of containing Soviet geopolitical expansion. But India was resolute in its non-alignment philosophy. So the US turned to Pakistan, which readily accepted the proposal. Immediately after Independence, Muhammad Ali Jinnah asked the US to provide some $2 billion in military and civilian aid to Pakistan, making the US potentially the largest donor for the fledgling economy. Between 1950 and 1954, the US funded the raising of five-and-a-half divisions, also referred to as the 51/2 Division Plan. (Crossed Swords: Pakistan its army and the wars within by Shuja Nawaz, Oxford University Press 2008. page 94)

Pakistan has historically been among the top recipients of US aid with the country receiving $30 billion in direct funding till 2011. Nearly 50 per cent of this has been for military assistance. The Pakistan military has evolved into a force with 19 infantry divisions (plus FCNA, or Force Command Northern Areas), two armoured divisions and two mechanised divisions with other supporting arms.

Proxy war in Kashmir theatre

The 1947-48 war, which is referred to as the first Kashmir war, brought out the concept of war by proxy. In this period, both the commanders-in-chief of the Indian and the Pakistani army were British officers under the command of Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck who was located in New Delhi. When the tussle over the control of Kashmir between India and Pakistan began in 1947, it was Pakistan Prime Minister Liaquat Ali who initiated the attempts to forcefully take over Jammu and Kashmir. The evidence of Jinnah’s knowledge of the tribal invasion is somewhat inconclusive. The plot was devised by a Pakistani army officer, Colonel Mohammad Akbar, who was commander-in-chief of the Azad forces and went under the pseudonym of General Tariq. He was known to be in close contact with Qayum Khan, and through him, with Jinnah.

Commander-in-chief of Pakistan Sir Frank Messervy had opposed the tribal invasion of Kashmir in a cabinet meeting with Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan in 1947. He was not taken with the idea of British officers in the Indian and Pakistani army fighting each other on the war front. However, in an informal conversation with some dignitaries, General Messervy viewed that ‘all it required was a battalion in plain clothes, who would have been there Srinagar within 12 hours. Two companies at the airfield in Srinagar and two at Banihal Pass, and that would be the end of the story’. This indicates that there was some underhand intent from the British to force Kashmir to join Pakistan. Messervy had told Akbar that ‘you will not have to do it with sticks alone any longer. I am going to help.’ He ended up allotting a million rounds of ammunition for the war and the release of twelve officer volunteers from the Pakistan Army for three weeks. (Crossed Sword by Shuja Nawaz)

It was Lieutenant-General Douglas Gracey who took over from Messervy in February 1948 who reportedly disobeyed direct orders from Jinnah, the Governor-General of Pakistan, for the deployment of the army units, and ultimately issued standing orders that refrained the units of regular Pakistan Army to further participate in the conflict. Lord Mountbatten agreed with Gracey. Thus rose the idea of war by proxy without the official sanction and use of the army. The Pakistan Prime Minister and Col Akbar secretly commenced the execution of their plan.

Tribal leaders and ex-servicemen, some belonging to the erstwhile Indian National Army (INA), were mustered and armed with weapons to invade Kashmir. In this, there was some supervision of Pakistani army officers, too. Incidentally, a proper appreciation was written by an officer (Colonel Sher Khan) of the military operations branch for this operation, which General Gracey had objected to. The initial phases were a great success, but the offensive lost its way when the raiders became more interested in looting.

The analysis was that had there been more discipline and a stronger command and control, Kashmir would have been part of Pakistan. The lesson was driven home when Gilgit-Baltistan was handed over to Pakistan by a British officer-in-charge of troops in the region. Two strategic lessons were learnt. First, a nation could go to war without using its army and officially denying its involvement. Second, mercenaries, motivated by ideology, had the potential to achieve far greater results with minimum costs involved. The strategy of hybrid war and the war by proxy has since become the mainstay of Pakistan’s Grand Strategy. The victory against the Russians in Afghanistan and the continued attempts to retake Kashmir have reaffirmed their faith in this strategy.

The offensive strategy of 1965

The war of 1965 revealed Pakistan’s offensive expansionist strategy. The strategy was designed for both the eastern and western borders of West Pakistan. East was to acquire Kashmir and towards the west, the idea was to control Afghanistan. Three factors induced Pakistan’s decision to execute the war of 1965.

First was Pakistan’s understanding, based on its intelligence from the hinterland of Kashmir that the Muslim population was in support of a takeover by Pakistan and would partake effectively in neutralising the Indian Army. Second was the 1962 India-China war, which suggested that the Indian Army was in a poor state and would not withstand an offensive by the Pakistanis. Third was Pakistan’s success in the Rann of Kutch action where the Indian higher command and control had shown distinct signs of weakness.

The strategy for the capture of Kashmir involved an initial phase of a proxy war to break the Indian administrative control inside the state, tie down the army and then launch a conventional war through an offensive to cut off the road links to the valley. The first part was Operation Gibraltar — a brilliant concept, based on the infiltration of trained guerrillas under Pakistan Army officers into Indian-held Kashmir to help foment local dissent and an uprising. They were then to take over the airfield and radio station and proclaim a revolutionary council, followed by a request for help from Pakistan. This would justify the war and be the signal for Pakistani forces to cross the ceasefire line to help the Kashmiris.

The second part of the plan, Operation Grand Slam, was to launch an offensive through Akhnoor, a key chokepoint on the only land route between India and Kashmir, and isolate the Valley. It was typically a hybrid operation with astute strategy. One of the assumptions was that the war would be limited to the J&K boundary. The whole strategy fell apart when India expanded the war to Lahore and towards Chawinda. Operation Grand Slam failed to achieve its stated aim. This was to be the story of the wider 1965 war with India as tactical brilliance and gallantry at the lower levels of the Pakistani command were nullified by a lack of vision and courage among the higher levels of leadership of the Pakistan Army. This was a recurring theme of Pakistan’s external wars as senior leaders failed their lower-level commanders and ordinary soldiers with poorly conceived military adventures, time and again. In the end, what was portrayed as a magnificent victory over India by Ayub Khan’s propaganda machinery, produced only disillusionment and catalysed his eventual fall.

The strategic riposte of 1971

The strategy of the 1971 war was a riposte from West Pakistan into the Indian territory, seeking to forestall an Indian decision in East Pakistan and draw international intervention. There was no strategy in East Pakistan because it was already lost in the failed handling of the situation, both politically and militarily. A CIA report read: “Many years of economic discrimination and political repression by the west wing had made the autonomous Bangladesh the choice of over 75 per cent of Bengali voters in the December 1970 elections. The refusal of Pakistan’s military leaders to honor that choice and their attempt to terrorize the Bengalis into submission have almost certainly ended any general desire in East Bengal to see the Pakistani union continue.” (Crossed Sword by Shuja Nawaz)

Pakistan had a two-phase plan for its operations in the western theatre. In Phase I, its formations from the north to south, were to attack with a view to protect Pakistani territory, while forcing India to commit its troops, particularly in northern Punjab and Kashmir. In Phase 2, a counterpunch was to be launched by 2 Corps in the area south of the Sutlej River, thrusting deep into the soft underbelly of the Indian Punjab and threatening its key towns as well as supply routes to Kashmir. The operation for Pakistan petered out very fast and they could not launch Phase 2 of their strategy. Critical analysis was conducted by the Pakistan Army, which concluded that the institutions of higher defence management were overshadowed by personalities and the inability of the seniors to orchestrate the battle at operational level. Hubris was the cause of failure.

The shift from offensive to defensive

In 1986, India conducted a war game, Operation Brass Tacks, which demonstrated a full-fledged war as opposed to a limited war with decisive victory for the Indian forces. This seemed to rattle the Pakistan Army. So, they conducted Operation Zarb-e-Momin with the aim to send a message to the Indians that Pakistan had the capability and resolve to carry out effective defence against Indian aggression, and carry the fight into Indian territory.

For the first time, the ‘defence’ component of Pakistan’s ‘offensive defence’ strategy became larger and an understanding came within the Pakistani security establishment that India was not a minor threat — a conventional offensive into India will lead to disaster. From here on, Pakistan began to compress the conventional war sphere, aiming to avoid a conflict. To do so, they enlarged their unconventional sphere (hybrid war) and expanded the nuclear threat by reducing their threshold and introduced the threat of tactical nuclear weapons. Hubris gave way to pragmatism. The Pakistan Army honed its skills of unconventional war in Afghanistan and raised a viable force of ‘holy warriors’ in the form of mujahedeen that it considers a strategic asset.

The strategic overreach: Kargil

Kargil was the unfinished operation of the Siachen loss of 1984. At that time, a plan was made to retake Siachen militarily but was shelved. General Pervez Musharraf was the Brigade Commander during the Siachen operation. Now, he was the army chief. So the plan was dug from the past.

The effect of Ziaist Islamic teachings had taken hold and influenced military behaviour to the extent that ‘cold military logic’ had been replaced by Islamic slogans and prayers — ‘By the grace of god, we will put 10,000 rounds over there and Inshallah the enemy will be routed!’ Again, the Pakistani top brass made the assumption that the Indian Army would not fight at this altitude and desolate the area. The strategy of proxy war was adopted. While mujahedeen from Pakistan and Afghanistan were brought in to occupy the heights in Kargil, the command and control remained with the Pakistan Army that also involved a fair number of regulars. The strategy was brilliant, but failed because the basic presumption that the Indians would not fight proved wrong. Another humiliation for the Pakistan Army and the military leadership.

The new concept of warfare

In response to India’s Cold Start doctrine, Pakistan devised a new concept of warfare, which brings out an even increased defensive mindset of its military leadership. It concedes that although some territory will be lost, the Pakistan Army must fight with all it has and achieve parity with India. They suggested that even a stalemate with India will be considered a victory. This new concept tends to counter the lack of time and the surprise inherent in Cold Start. Considerable value has been given to unconventional warfare and even the concept of tactical nuclear warheads has been brandished to deter the Indian offensive. The conventional offensive content is minimal but they continue to maintain a strong offensive formation as a deterrence.

Strategy of alliance

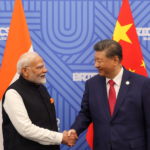

With the realisation that it has little chance of winning a conventional war with India, Pakistan has moved to the strategy of deterrence with acquisition/development of strategic nuclear and unconventional weapons. Attempts are being made to completely close the conventional war window by leveraging their geo-strategic potential. Pakistan, now, has the US and China as allies. It is balancing the act very astutely by knowing that both the superpowers need its services in the future struggle for global dominance. As long as one plays ball with Pakistan, it is assured of security.

The Pakistan Army has travelled down the strategy lane, commencing with a martial pride and hubris, which made them believe that they were the best fighting army of the world. And with Islamisation of the force, they believed that god himself had sanctioned their victory, both, in life and death. Being ‘offensive’ was Pakistan’s way of life — the hubris led to gross miscalculations, bringing a number of humiliating defeats, and slowly the knowledge that their fighting machine was not as efficient as they thought it was. The emotion of humiliation brings negative behaviour and unethical forms of warfare, one of them is resorting to terrorism. Today, Pakistan is unsure of the defence of its territory and is cultivating religious mercenaries with barbaric values to achieve an unattainable goal. The Pakistan Army has, time and again, led its people to humiliation but manages to retain power over them— by depriving them of education and keeping them religiously caged.