The geopolitics of hegemony and why the Indian Navy regards the Gateway of Tears as critical

By Vikas Gupta

Defence News of India, 28th Dec 23

The year is ending with the Indian Navy’s recovery of a Liberian flagged tanker, Motor Vessel Chem Pluto, which had apparently been attacked by an armed drone on Saturday after it crossed the West Asian straits and was entering the Arabian Sea. Given the recent spate of attacks on merchant shipping in the Arabian Sea, the navy announced the deployment of three guided missile destroyers – Indian Naval Ship (INS) Mormugao, INS Kochi and INS Kolkata – to maintain a deterrent presence. In addition, the navy’s P-8I Poseidon long range maritime reconnaissance aircraft are flying patrols over these waters in order to maintain maritime domain awareness.

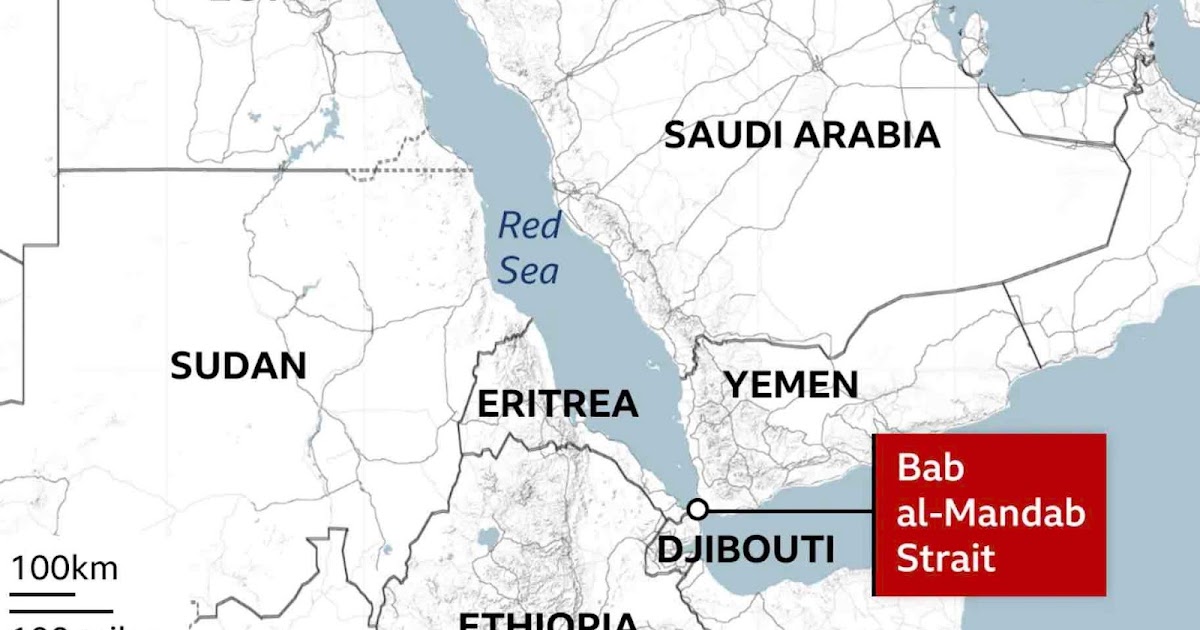

There are three key maritime chokepoints through which shipping can enter from West Asia into the Arabian Sea: the Suez Canal, the Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb (BAM). Almost all the oil and petroleum products being shipped out from the Middle East must pass through the chokepoint of the Strait of Hormuz. From here, giant tankers carrying petroleum products from the Persian Gulf head east for Asian markets – primarily China, India and Japan – without needing to risk navigating the BAM or the Red Sea.

Of even greater interest to New Delhi is BAM’s role as a strategic link between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea and the Suez Canal. The strait is 18 miles wide at its narrowest point, limiting tanker traffic to two 2-mile-wide channels for inbound and outbound shipments. Most petroleum and natural gas exports from the Persian Gulf that transit the Suez Canal pass through both the Bab el-Mandeb and the Strait of Hormuz.

The chokepoint’s Arabic name – the Gateway of Tears – illustrates its fraught geopolitical environment of inter-state and inter-sectarian conflict, state failure, famine and crime. The Indian Navy regards BAM as critical, given its commanding location astride the international shipping routes between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean. Closure of the BAM could prevent tankers originating in the Persian Gulf from transiting the Suez Canal, forcing them to divert around the southern tip of Africa, which would increase transit time and shipping costs.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic forced a re-calculation of oil and trade flows, some 6.2 million barrels of crude oil, condensate, and refined petroleum products crossed through the BAM every day. The strait’s two-mile-wide shipping lanes allow cruise ships, warships, fishing trawlers and international merchant shipping to keep going through the world’s fourth busiest waterway. The US and its allies have determined that safeguarding these sea lanes is in the global interest.

Since the early 1990s, pirates operating from bases in war-torn Somalia, emerged as a threat to international shipping in these waters. As piracy off Somalia and the Gulf of Aden became a veritable industry, insurance companies hiked their premiums in response, resulted in delayed delivery of shipments and increased shipping expenses. By 2011, piracy was costing global trade $6.6 to $6.9 billion every year.

The international response was not slow in coming. In the first decade of the new century, warships from various navies began escorting merchant shipping passing through these waters.

In December 2008, Operation Atalanta, originally known as European Union Naval Force (EU NAVFOR) Somalia, became the first naval operation conducted by the European Union in support of a United Nations Security Council resolution. It consisted largely of joint patrolling and coordinated escort operations by several European navies.

The mission, which was launched to protect oil and cargo vessels and shipments in the waters off Somalia, became one element of an international effort, in cooperation with the multinational Combined Task Force 151 of the US-led Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) and NATO’s anti-piracy Operation Ocean Shield.

Since 2013, deterred largely by Indian and Chinese warships and by EU Navfor Operation Atalanta, pirate attacks began decreasing.

Enter the dragon

Meanwhile China, under the guise of anti-piracy operations, has maintained a continuous presence in the Indian Ocean region. According the Manohar Parrikar Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses, China has deployed 120 warships off the Horn of Africa since 2008.

“At any point we have anything between five to eight Chinese Navy units, be it warships or research vessels and a host of Chinese fishing vessels operating in the IOR [Indian Ocean Region],” said India’s navy chief, Admiral R Hari Kumar in a lecture in New Delhi. “We keep a watch on them and see how they are undertaking their activities in the IOR.”

The navy chief says that China has used its counter-piracy effort around the Gulf of Aden as a rationale to set up its first overseas military base. Located in Djibouti. in the strategic BAM Strait, the base has cost $590 million (Rs 4,711 crore). Chinese warships located in Djibouti dominate the approach to the Suez Canal. However, Beijing maintains that Djibouti has been built as a rest and recreation facility for its naval personnel carrying out anti-piracy missions in these waters.

In addition to Djibouti, the PLA(N) is developing a presence in various ports in the IOR: Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Pakistan and now, in other countries as well.

India’s naval response

The Indian Navy, which regards itself as the “net security provider” in the IOR, has also stepped up to the plate, with a warship stationed at all times off the Gulf of Aden for counter-piracy tasks. The navy chief has said that 91 Indian warships have been deployed in the region since 2008, patrolling high risk areas where piracy was rampant.

In addition to anti-piracy missions and owing to heightened tensions in the Straits of Hormuz, Indian warships have also deployed to the Gulf since June 2019, under the aegis of Operation Sankalp, to reassure Indian merchant marine vessels transiting the region. During this period, 27 Indian warships have escorted 381 Indian-flagged merchant vessels carrying 305 lakh tonnes of cargo.

On its website, the navy says: “The Indian Navy has been deploying [at least] one ship in the Gulf of Aden on anti-piracy tasking since October 2008. The Indian Naval ships escort merchant ships through the 490 nautical mile-long Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC) and thus far 50 Indian Navy warships have been deployed.

The navy’s website goes on to state: “As on 15 Mar 2015, a total of 40 [piracy] attempts have been successfully thwarted by the naval ships on patrol. Indian Navy has safely escorted 3,075 merchant ships manned by nearly 22,448 Indian sailors as on 15 Mar 2015.”

In August 2016, India and the US “operationalised” an agreement for reciprocal logistic support, termed the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA). Since then, Indian warships have been taking fuel from US tankers during anti-piracy patrols [near the Horn of Africa].

New Delhi has been deliberate in displaying leadership in carving out a role in counter-piracy. Squeezing a high volume of merchant and military traffic through narrow channels is just the first challenge. Then there is the question of who is to lead collective security, since the area is bordered mainly by weak countries that are focused mainly on their internal security. With the Covid-19 pandemic sapping regional attention and resources and leaving little mind space for maritime security, there has been a sharp increase in piracy in 2020.

While the CMF has the flexibility, skills, and credibility to take on a larger role in the BAM, the US does not favour greater involvement. Beijing’s muscular approach could backfire unexpectedly. Fragile Yemen could splinter further, encouraging the Houthis to act more aggressively in their own waters.

West Asian geo-politics

Meanwhile, across West Asia, competing national identities, ethnic rivalries and sectarian interests complicate inter-state relations. Persian – Arab – Turk ethnic animosities continue to provide an overarching competitive framework. The Shia Arab-majority states and groupings such as Iraq, Syria, the Hezballah, Hamas and the Houthis in Yemen remain tightly linked with Shia Iran; even as the leader of the Sunni world, Saudi Arabia, walks a fine line in its relations with Israel and the Shia world.

Meanwhile, Turkey is quietly building a presence in Yemen, backed by both Qatar and Oman. Tehran has stated it supports the Houthis politically but denies arming the group. The Arab world’s political powerhouse, Egypt, is suffering financially from the unexpectedly low passage through the expanded Suez Canal, by Covid-19 depressing world trade and by Russia luring shipping to the Arctic route.

Given the complexity of the situation for New Delhi, analysts are recommending seizing the initiative and establishing hegemony or collective security in the Red Sea. With Covid-19 distracting global attention and the security of the BAM increasingly fragile, the risk of a dangerous miscalculation is high.

Beijing, meanwhile, is treading carefully, avoiding involvement in the rivalries around BAM. This neutrality allows it to cultivate its economic and diplomatic relationships in the Middle East and Africa without alienating any potential partner countries. Unless China’s economic or strategic interests are severely threatened, it is unlikely to take an overt role in resolving the regional conflicts around the BAM. Since most regional countries are already committed to longstanding partnerships of their own, any Chinese attempt to secure the BAM via naval control would have to go it alone, a gargantuan effort with questionable returns.

Turkey may take advantage of the chaos to entrench itself further in the region; even if President Erdogan could work effectively in a complex conflict zone. Saudi Arabia’s support to the US could rapidly fade, especially if it opened up Saudi Arabia to further Yemeni attack.

Finally, Eritrea, Djibouti and other weaker regional states have limited wherewithal to do much, but perceived threats to their sovereignty from US-led military actions in the region could push them further into China’s arms.

So how best to secure the West Asian sea lanes? In the past, this has been achieved by a muscular approach combined with one that has addressed the root causes of piracy. The suppression of piracy off the Horn of Africa relied on the appearance of an overt international naval presence; a big grey ship on the horizon tended to result in a sudden change of plans by would-be pirates.

From its first major base beyond its own waters, China will be looking at the lessons learned in the Middle East Region about how Western forces react in volatile situations. Other actors will also be looking at how much of a role the US and its partners take in the BAM, and adjusting their actions accordingly.

An increased – and increasingly visible – presence by the U.S. and its partners is warranted, leveraging existing partnerships and working with new and inexperienced partners. Activities such as passing exercises, boarding practice, and sailing in company help build regional capability and confidence, or at least keep some of the less professional navies out of trouble.

A similar approach is used in the Persian Gulf via the CMF’s Combined Task Force (CTF) 152, but this does not necessarily make it a suitable blueprint. Led by local states for most of the past 10 years, CTF 152 is tasked with regional maritime cooperation between Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

Instead, a U.S. coalition should take the lead in a more overt naval presence. While China has pursued a carefully crafted and long-term military engagement in Africa, including sales of increasingly sophisticated military equipment, military engagement with the countries around BAM has been patchy at best.

The security situation in the Persian Gulf and BAM does not look like it will be resolved any time soon; indeed, with the multiplying effects of pandemic, economic collapse and plunging oil prices, it is likely to get worse.

The Houthi connection

For weeks, beginning soon after Hamas fighters in Gaza launched coordinated attacks on Israel on October 7, rebels from the Iran-backed, Shia Muslim, Houthi group in Yemen have unleashed multiple airborne strikes on cargo ships traversing the Red Sea and the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb, leading many of the world’s biggest shipping companies, including Mediterranean Shipping Company, Maersk, Hapag-Lloyd and British Petroleum, to announce they would avoid the area. This has caused oil prices to rise, damaging the global economy.

The Houthis are Zaidis, a sub-sect of Yemen’s Shia Muslim minority. They consider Iran as an ally, because Saudi Arabia is their common enemy. They take their name from the movement’s founder, Hussein al Houthi. The group was formed in the 1990s to combat what they saw as the corruption of the then-president, Ali Abdullah Saleh.

President Saleh, backed by Saudi Arabia’s military, tried to eliminate the Houthi rebels in 2003, but the Houthis repelled them both. Since 2014, the Houthi rebels have been fighting a civil war against Yemen’s government. By the start of 2022, an estimated 377,000 people had been killed.

Washington has earlier announced the launch of a multinational force, involving more than 20 countries, to protect vessels transiting the Red Sea. But without a clear and coherent plan the bloodshed and killing will continue.