SOURCE: The Tribune

The final round of the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA) Alfa dogfight trials took place on August 20. The trials aimed to “demonstrate advanced AI (artificial intelligence) algorithms capable of performing simulated within-visual-range air combat manoeuvring, colloquially known as a dogfight.” Eight teams participated in the event, and the winning team, Heron Systems, squared off against a top

F-16 pilot. The AI pilot won 5-0.

Although the simulation was a simple one-on-one scenario and did not imply that AI is ready to replace pilots, it demonstrated that an AI agent could effectively learn and successfully apply basic fighter manoeuvres. A DARPA official said, “This was a crucible that lets us now begin teaming humans with machines… where we hope to demonstrate a collaborative relationship with an AI agent handling tactical tasks like dogfighting while the onboard pilot focuses on higher-level strategy as a battle manager supervising multiple airborne platforms.”

Technology has always played a crucial role in warfighting and the character of war. However, some sceptics state that the impact of technology is overrated. They point out the failure of a network-centric US military to defeat the insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan. There is a similar discussion in India on how far technology can overcome the challenges posed by the terrain along the Himalayan watershed or in areas like Siachen.

There is no doubt that the quality of human resource, levels of training, motivation, and human ingenuity will be major war-winning factors. But we must also recognise that today, technology is having a more transformative impact on the world than ever before. Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum, in his book The Fourth Industrial Revolution, writes that the most critical challenge today is to understand the “speed and breadth” of the technology revolution. Many of the emerging technology breakthroughs are in their infancy but are “already reaching an inflection point in their development as they build on and amplify each other in a fusion of technologies across the physical, digital and biological worlds.”

We are yet to grasp all the implications of this new revolution fully, but it is clear that emerging technologies, while empowering individuals and societies, are also disrupting traditional models of business, governance, and even social interaction.

The ‘empowerment-disruption’ effect is equally real for warfare. There is a blurring of lines between war and peace as hybrid conflicts take centre-stage. The distinction between civil and military technologies is disappearing with the diffusion of technologies, resulting in non-state actors increasingly getting access to lethal weapon systems. Saudi Arabia is among the top five countries globally in military expenditure, yet it has been regularly attacked by drones and missiles fired by Yemen Houthi rebels.

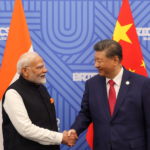

The Indian military faces the twin challenges of an assertive China and stressed budgets. In view of this, there is little option but to look at capability enhancement through greater adoption of technology. However, there is still some hesitation in the military to move firmly in this direction. The military leadership has grown up with and is comfortable with the existing organisational structures and systems. There is an understandable reluctance to lessen the reliance on high-value monolithic platforms like tanks, battleships, and manned aircraft that have served us well in the past.

While it is clear that the fighter pilot and the tank may not disappear soon from the battlefield, it is equally clear that these are decades-old systems, and there is a limit to how much incremental technology can be applied to make them more potent. In future capability building, we should be aiming for transformational change, not incremental.

One more reason why emerging technology is attractive is that the development and operating cost of traditional military platforms are becoming prohibitive. The development cost of the F-35 aircraft is $400 billion and the cost to own and operate the entire F-35 fleet over its expected 60-year lifetime is a staggering $1.12 trillion. This is prompting countries to explore the option of low-cost but highly networked systems to defeat conventional weapon systems.

In looking at the future, we need to have clarity on areas of technology focus and the approach to be followed. The adoption of advanced technology is uniformly low in the three services, and while this is worrying, it also provides us a second-mover advantage. We could learn from the successes and failures of others and move straight into areas of technology that offer revolutionary progress.

Michael O’Hanlon, in his study Forecasting Change in Military Technology, 2020-40, looked at 39 categories of military-relevant technologies. Of these categories, he found that revolutionary advances are most likely in artificial intelligence, computer hardware and software, internet of things, offensive cyber operations, robotics and autonomous systems.

It is evident that the most revolutionary changes are likely to come in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector. To exploit this, we must leverage our considerable talent and skills that exist in the civil industry and academia. Relying on government R&D institutions that are neither agile nor innovative in ICT could be counterproductive.

The Indian industry can help build trusted networks based on indigenous hardware and software. Our military will inevitably become more networked in the future, and if these networks are built on foreign hardware and software (as is currently the case), there is a huge vulnerability that can easily be exploited by our adversaries.

Even in robotics and autonomous systems, there is considerable expertise and adoption in the civil industry. Research in autonomous vehicles is more advanced in the auto industry than in the military. Here again, industry knowledge needs to be utilised. Where the defence R&D can play its role is in funding the AI-based backbone that enables relatively inexpensive commercial systems to be employed as a networked attack swarm with a degree of autonomy.

The fourth industrial revolution is already here. It demands a faster embrace of future technologies and a change in our traditional reliance on government organisations to lead the military R&D effort.