SOURCE: HT

The India-China standoff in Ladakh persists even after multiple rounds of commander-level talks and two ministerial meetings between the defence and foreign ministers of the two countries. This amounts to India living with the Chinese encroachments since May. That there was no reference to reverting to the status quo ante in the joint statement after the foreign ministers met in Moscow suits China well.

China’s military obduracy in the Himalayas reflects its assertion as an emerging Asian hegemon and expansionist power. Many of its neighbours have experienced the effects of this. However, the Ladakh situation is not just about China asserting its dominance.

The Aksai Chin region has a strong strategic value for China. In the late 1950s, when it first transgressed into Aksai Chin, the then Chinese premier, Zhou Enlai made a proposal to accept India’s hold over Arunachal Pradesh (then called North East Frontier Agency) in return for Chinese control over Aksai Chin. This region of Ladakh was critical to China to shield its turbulent periphery of Tibet and Xinjiang.

China also, subsequently, deepened its links with Pakistan, which handed over parts of Indian territory under its occupation to China. This partnership has only grown, with Beijing now having invested billions of dollars to consolidate its strategic outreach. China’s officially blessed commentators often highlight the significance of Aksai Chin, and the centrality of Pakistan in the region.

It was in this backdrop that India’s stated intent to recapture Aksai Chin rattled the Chinese. Union home minister Amit Shah’s statement in Parliament, in September 2019, after changing the status of Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir to Union Territories, may be recalled: “Kashmir is an integral part of India. When I talk about Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and Aksai Chin are included in it…We will give our lives for this region”. China strongly questioned this statement and has refused to endorse the new status of Jammu and Kashmir.

The fate of mutually-agreed non-escalation between India and China will depend on the Chinese side. China will try to sustain the standoff by all means possible. Diplomatically, Beijing is keenly awaiting the outcome of the United States (US) presidential elections and hopes that a Joe Biden victory will open a window of opportunity to soften US hostility.

China is also preparing to further pacify the Japanese approach towards it under Prime Minister (PM)?Yoshihide Suga. Japan has heavy economic stakes in keeping the peace with China and Suga, unlike his predecessor Shinzo Abe, may also like to steer clear of the deepening US-China rivalry.

This may sound speculative at the moment, but geopolitics often shifts radically. China’s success with the US and Japan will be bad news for India. An internationally-emboldened China could be far more aggressive towards India. In China’s perception, India is asserting itself against Chinese moves in the Himalayas only because it is backed by the US and its allies. India has to carefully monitor and adequately respond to such developments. PM Narendra Modi’s conversation with PM Suga, in this context, is a welcome initiative.

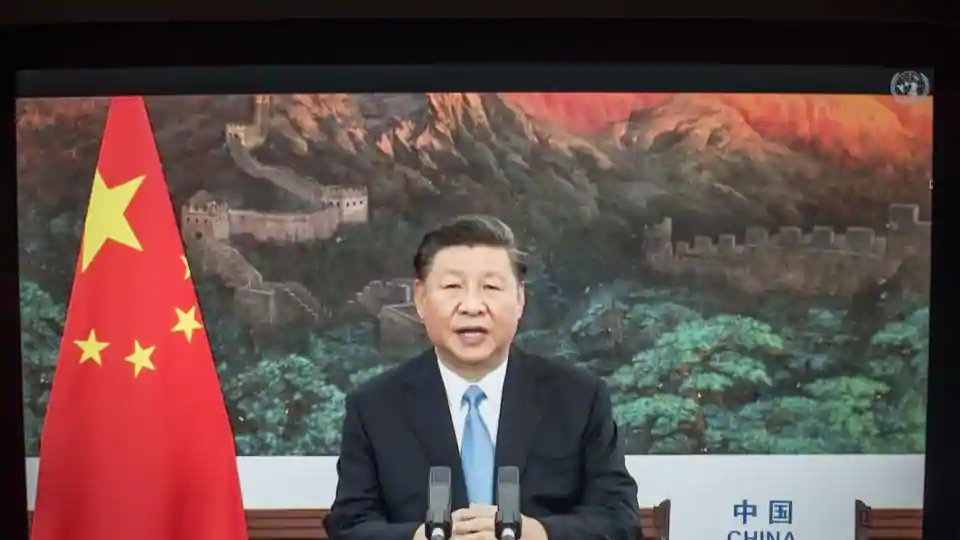

The theories that the Ladakh moves are primarily led by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which is not comfortable with President Xi Jinping and the Chinese political establishment, are untenable. Xi is the chief of China’s military command and the massive movement of troops in Ladakh by PLA could not have taken place without his endorsement. Xi, at the Seventh Central Symposium on Tibet (August 18-29), also made a strong policy move on Tibet, asking for developing a “new socialist Tibet”, where its Buddhism must conform to the “Chinese context”. This, in Xi’s approach, would be done by taking the Tibetans away from the Dalai Lama, changing their Lamaistic religious and social practices, and integrating them closely and ethnically with mainstream China.

This approach aims to control Tibet in three principal ways. One, to cut off its external linkages and deflect international pressure on Tibet; two, change its demographic composition, and; three, institutionalise mass surveillance. This will be on the lines of similar repressive moves in Xinjiang.

The massive military movements and deployments of Chinese forces in Ladakh and the projection of a so-called Indian military threat will help in this repression. The standoff is thus in China’s internal political interests of stability in Tibet. One wonders if China is doing this out of enhanced confidence that it can control Tibet or a lurking sense of vulnerability in the context of a post-Dalai Lama Tibet.

Xi is also using the Ladakh standoff in his internal political campaign of silencing critics who are cautioning him against hostility towards India and other neighbours, while the principal challenge is to confront the US. The official media has also projected the Ladakh conflict as an answer to India for the so-called setback in Doklam. It has been woven into China’s resurgent territorial nationalism. The local media plays up the idea that India is too weak to stand against China’s might. There does not appear to be any easy way out of this Chinese domestic political dimension of the Ladakh stand-off. There is a reactive internal political dimension to the military situation in India as well. It is seen as a defence for the changed status of Jammu and Kashmir and is also linked to India’s resurgent nationalism, where any plea for moderation on the border with China will come in for criticism.

One wonders if the internal political dimensions can be decoupled from the Ladakh standoff through a summit meeting between Modi and Xi. Or, will there be hostilities in the Himalayas again?