SOURCE: THE WEEK

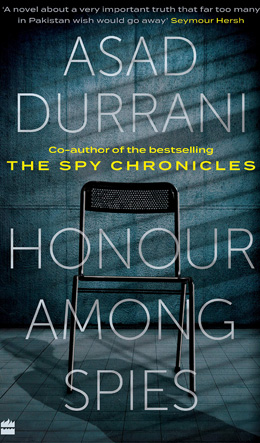

Pakistani Lieutenant General Asad Durrani is no stranger to controversy. The first book written by the former head of the Inter-Services Intelligence, The Spy Chronicles: RAW, ISI and the Illusion of Peace, created history. It was written with former head of Research & Analysis Wing A.S. Dulat. Durrani was put on Pakistan’s Exit Control List and his pension was scrapped. His second, Pakistan Adrift, was blunt too. The army tried to stop it from being printed and failed. His latest, however, is potentially explosive.

Honour Among Spies is a clever thriller that is a thinly disguised account of his experiences after his first book. There are no secrets revealed, but there are uncomfortable truths that he hints at, about the powers that be.

It is clear: the hero Osama Barakzai is him. Jabbar Jatt is the chief of army staff General Qamar Bajwa. “I want [readers] to come to that conclusion,” Durrani tells THE WEEK over the phone.

He uses fiction to give credibility to what is an open secret in Pakistan. That Jatt propped up Khurshid Kadri “a showman-turned-politician”, referring to Prime Minister Imran Khan. Durrani’s book proves that conspiracy theories can be real, too.

What makes the book thrilling is the way Durrani used fiction to outsmart those who are out to get him. “Soon after retirement from the Pakistan Army, I picked up the pen?arguably mightier than the sword unsheathed,” he writes in the author’s note.

The book comes at a time when there is a political storm brewing in Pakistan. Imran Khan is facing the might of a united opposition, and former prime minister Nawaz Sharif is making the same accusations as Durrani—of Bajwa being responsible for the toppling of his government, of corruption and interference of the deep state. Excerpts from Durrani’s chat with THE WEEK:

Honour Among Spies is a very brave book to write.

One made an effort. Because it was such an unusual experience one went through, it was worth writing about it.

Are you afraid of the repercussions?

I have no idea what the repercussions will be. One has to be ready for anything. Regardless of where you are and what position you are in, if there is a message you think you must convey to people, then you should.

The real problem was not the book. That is what Honour Among Spies should convey. There are people who carry a history, a very uncomfortable history and there are some people who can be very uncomfortable with that.

In the book, there are parallels that are difficult to miss. The main character is like you. Jatt seems to be Bajwa. Your comment.

Anyone who reads it will straight away come to that conclusion. I want them to come to that conclusion. I still belong to that institution, which produced different types of people. If it is possible that someone like him should also be there, let people know that such things can also happen. It is not unprecedented.

This is a pretty big risk to take in Pakistan, right?

Anywhere, perhaps. If it is a big thing to do, then it had to be done. Someone has to bell the cat. I got the opportunity to do it. I did not volunteer to do it.

Your book also has a character like Osama bin Laden. This is not the first time you have made the claim that Pakistan was complicit in sheltering him.

That chapter was closer to the truth than anything else in that book. One of my colleagues was provided official access. He was not going to talk about everything he saw. But his conclusion was: “Yes, we, Pakistan, preferred incompetence over complicity.”

In May 2011, without knowing what had happened I made my assessment and said it could not have happened without our help. I can understand why we would deny [complicity]?to avoid political embarrassment. I did not want to say we are incompetent. Till today, I am not claiming that I know what happened.

You theorise that the Iran strike on the US’s Iraqi airbase after the murder of Qasem Soleimani was an eye-wash. To avoid a conflict. Osama, in the book, claims that the surgical strike by India too was a face-saver. Is this also conjecture?

No. Dulat and I talked about Uri. We came to the conclusion at that time that there must have been understanding and some wisdom to say that if it has happened, at least it can diffuse a particular situation.

As for the Middle East, it has happened twice. A Syrian base was once hit five years ago, too. My German friends said Israel, Russia, etc were on board. It was a smart thing to do.

At this point in the India-Pakistan relationship, when both sides are so bitter, do you see any possibility of any understanding?

There is certainly a possibility. In the present circumstances, if we [ask, can] things get worse, yes, they can. It is not that war can start. The war is already on. It has been on all the time. It can get intensified like with [the death of] Burhan Wani or [abrogation of article] 370. [But] conventional war will not happen.

Do you think Track II diplomacy has meaning anymore?

Track II is a circus. We started it after the nuclear tests in 1998. I have taken part in some of them. Islamabad and Delhi are not waiting for us to come back and tell them what to do after a Track II event. The beneficiaries of Track II, apart from people like me who can go and participate, are the sponsors. They get a good report.

What will happen to Jatt and Kadri?

I do not know. For a long time, one has avoided following the domestic political front. In the last two or three years, I feel that [we are] gradually drifting in a direction, and some major course correction will need to happen. I do not see a sustainable process. It does not have to do with Jatt or Kadri. It is because in a dual system, people do not know how to take responsibility.