SOURCE: THE WEEK

The armies of India and China are continuing their standoff along the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh. One country has been watching the tension from the sidelines with anticipation: Pakistan, which describes China as its “all-weather ally”. While Pakistan’s government has made little noise on the Ladakh standoff, on social media, Pakistani voices have been taunting India.

Sixty years, Pakistan’s perception of China’s role in the region was very different. In the 1950s, Pakistan was an ally of the US and offered bases in the country for US spy flights into the Soviet Union. China even claimed parts of Hunza and Gilgit, which lie in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, as its territory.

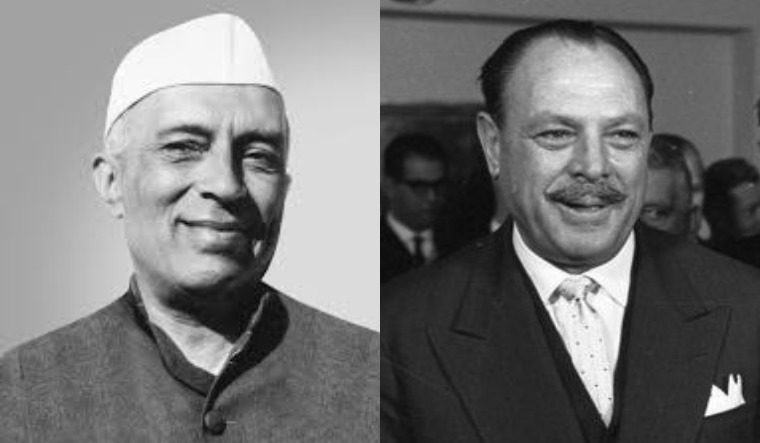

Pakistan’s first military ruler, field marshal Ayub Khan who seized power in a coup in 1958, was wary of expansionism by Communist China. One of the measures he suggested to contain this would sound improbable today: A joint defence agreement with India.

J.N. Dixit, who served as national security adviser in the first Manmohan Singh government, wrote about the evolution of the ‘joint defence agreement’ proposal of Ayub in his 2002 book India-Pakistan in War and Peace.

In the book, Dixit writes Ayub raised the proposal for a joint defence pact on April 24, 1959. The previous month, March 1959, the Dalai Lama had fled Tibet amid a brutal Chinese crackdown to asylum in India.

Dixit quotes the Pakistani ambassador in Tokyo, Mohammed Ali, as saying on April 20, 1959, “The Tibetan issue has jolted Asian people out of their complacency,” adding that the issue should open the “eyes of Asia to the danger of red imperialism”.

From 1953, Chinese troops carried out localised intrusions into Hunza. In 1959, Ayub Khan declared, “any Chinese intrusion into Pakistan territory would be repelled by Pakistan with all the force at her command”.

India’s first prime minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, rejected Ayub’s proposal. Speaking in the Lok Sabha in May that year, Nehru said, “… we do not want to have a common defence policy, which is almost some kind of military alliance…” Dixit notes Nehru may have been wary about the joint defence agreement by Ayub as he saw it as a means to push for a compromise on Jammu and Kashmir.

Interestingly, in 1949, Nehru had proposed a ‘no-war’ pact with Pakistan after the invasion of Jammu and Kashmir in 1948, which Islamabad rejected.

Ayub himself confirmed in September 1959 that a “prerequisite” for his joint defence proposal was the “solution of big problems like Kashmir and the canal waters”. Some scholars have even opined that the joint defence pact proposed by Ayub was one of the points of disagreement between then Indian Army chief general K.S. Thimayya and Nehru.

Transcripts of a conversation in February 1963 between Aziz Ahmed, Pakistan’s ambassador to the US, and US officials showed the practical plans for such a joint defence agreement. “If Pakistan took on the responsibility for the defence of Ladakh, it would result in a real joint defence of the subcontinent—i.e., Pakistan would defend the western flank, consisting of Kashmir and Ladakh, and India would defend NEFA (North East Frontier Area),” US State Department archives quote the Pakistan ambassador as saying.

Moreover, other ‘players’ were also keen on such a defence agreement. Following the Indian Army’s humiliation by China in the 1962 war, the US and UK offered to help India strengthen its military. A letter from then British prime minister Harold Macmillan to then US president John F. Kennedy, dated December 13, 1962, emphasised the UK’s view of a joint defence pact.

Macmillan wrote, “what sort of army should the Indians have to fill the major role of defending themselves against an all-out Chinese invasion? It is clear to me that any sensible defence, on whatever scale may be agreed, can only be effective if it is organised as a joint Pakistani-Indian plan to defend the subcontinent as a whole. This would be far more effective, less wasteful of troops, and would avoid our chief difficulty which is how to help the Indians without correspondingly upsetting the Pakistanis who are loyal friends and members of the CENTO and SEATO pacts.”

Macmillan noted that the status of the Kashmir problem was central to the success of any pact between India and Pakistan. “In any agreement Pakistan must obviously keep the part of Kashmir she at present occupies (with perhaps some adjustments) and the Indians must keep Jammu and Ladakh. The problem centres on the vale of Kashmir. A plebiscite will never be accepted by the Indians. It is just possible that they might agree to the vale of Kashmir becoming an autonomous state guaranteed by both India and Pakistan,” Macmillan wrote.

However, prospects for a joint defence agreement began to fade in the years following 1959 as Pakistan and China built ties and made efforts to address their boundary dispute, with Islamabad seeking to take advantage of the deterioration in Sino-India ties.

A Brookings Institution study noted, ” Pakistan President Ayub Khan told Kennedy that he wanted ‘compensation’ from India in Kashmir for Pakistan’s neutrality during the [1962] war”. Bruce Riedel, a former CIA official, even claimed in his book JFK’s Forgotten Crisis: Tibet, the CIA and the Sino-Indian War that Kennedy stopped Ayub Khan from attacking India during the 1962 war.

In March 1963, China and Pakistan formalised a border settlement, in which Pakistan ceded 5,180 sq km of territory in PoK to China. India still maintains this transfer of land to China was illegal. The 1963 boundary agreement is considered a milestone in China-Pakistan ties, which paved the way for China becoming Pakistan’s strongest strategic ally and its main supplier of weaponry.

https://defencenewsofindia.com/when-nehru-rejected-pakistans-offer-of-joint-defence-pact-against-china/