SOURCE: OUTLOOK INDIA

Who has not heard of the vale of Cashmere,/ With its roses the brightest the earth ever gave/ Its temples, and grottos and fountains as clear/ As the love-lighted eyes that hang over their wave? Even before the West’s fashionable women—from aristocrats to demi mondes—were to be in thrall of its exquisite Pashmina shawls, Lalla Rookh (1817), the extravagant Orientalist fantasy by Thomas Moore about the adventures of a daughter of ‘Aurungzeb’ on her way to Kashmir to wed the King of Bucharia, made ‘Cashmere’ a byword for beauty. Yet few Europeans had actually set eyes upon its mythical charms; still under Afghan rule, it was shut off to foreigners.

That started to change in 1819, when Ranjit Singh conquered the province. After his death in 1839, his Sikh empire was riven with corruption, factionalism and bloodletting…and the 1st Anglo-Sikh War followed a mere seven years later. The Sikhs were comprehensively defeated, with the Bengal Army occupying Lahore, but the British were in a mood of benevolence, and Lord Hardinge, the governor-general, wanted a buffer Sikh state. Benevolence came at a cost: an indemnity of a million pounds had to be paid, and there was no money in the treasury.

A tributary chief, Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu, offered to pay up—in return for the Kashmir Valley, Ladakh, Gilgit-Baltistan and Jammu. Thus came to exist the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, which would last 101 years, over four rulers.

Kashmir settled down to an (externally) placid existence under the Dogra kings, a ruling class imposing themselves on a mostly poor population and maintaining excellent ties with a succession of watchful British residents. The latter let them be, for Kashmir was soon to be a station of rest and recuperation. The famed houseboats of Kashmir, moored on the heavenly Dal Lake, arrived around 1875, catering to Europeans who lazed on them, taking their tea and gazing on the snowy ramparts of the Zabarwans. They took to the water chiefly because Gulab Singh, fearing a British influx, forbade Europeans from owning land there—an early manifestation of that inflexible rule. Soon, like in Simla, scandalous things were afoot, so much so that it took the iron-willed, Bible-and-sword wielding John Nicholson—famed Punjab ‘political’, fierce soldier and moraliser—to pay a visitation and ‘purify the moral atmosphere’ (perhaps aptly, Nicholson, leading the charge at the British retaking of Delhi in 1857, died at the Kashmiri Gate).

Yet, throughout the 19th and till the early 20th centuries, Kashmir was to be the still centre, an untarnished pearl around which raged a gigantic geopolitical tussle for supremacy. The British, French and others might have spectacularly grabbed realms in Asia and Africa, but in terms of territory gained, it was dwarfed by Russia’s Central Asian acquisitions. By the turn of the 19th century, with the Siberian vastness firmly in the Tsar’s doublet pocket, it turned its gaze towards the Caucasus and elsewhere. Just as British dominion in the subcontinent expanded manifold between the 1820s and 1890s, new Russian maps now included the Caspian Sea, its eastward swathe up to the borders of Chinese Turkestan, and the edges of Persia, Afghanistan and Tibet in the south. For the first time ever, the boundaries of the British and Russian Empires—separated by thousands of miles a generation ago—faced each other.

Russia’s ultimate objective was thought to be India—that it was Britain’s golden goose was never in doubt—so Afghanistan, Kashmir and its northern reaches, and Ladakh as well as Tibet by extension were considered the bulwarks, to be defended at any cost. Fears of a Russian invasion took hold of London and Calcutta in stages, before it turned into a national obsession. ‘The Great Game’—the jaunty name to a century’s worth of machination, expedition, scholarship, skulduggery and soldiery, consuming vast amounts of energy, money and lives—was given by Capt Arthur Connolly (1807-43), a soldier-explorer who sacrificed his life on this sinister playing field.

Early warnings were sounded by strategists like Sir Robert Wilson (in Sketch of the Military and Political Power of Russia, 1817), and by the Company’s ‘superintendent of the stud’ William Moorcroft, who in the guise of the search for the perfect horse for the cavalry, journeyed into Tibet (1812) and across Kashmir, Ladakh, Punjab, Afghanistan to fabled Bokhara (1819-20). An expert intelligence scout, his reports went to the Political and Secret Department, headed by his friend, Delhi’s own Charles Metcalfe. In 1820, he was the first Englishman to enter Ladakh. He was turned away when he entered western Tibet, and saw them as trading launching pads to Central Asia—a backdoor to China and, as a frontier to Russia to the north, of great political interest. He also noted the intrusion of Russian agents and traders and their efforts to force open trading rights from the north, and the monopoly of Kashmiris in the purchase of the prized Pashmina wool from Ladakh and Tibet. In Kashmir in 1822-23, Moorcroft noted the misery of the people under their new Sikh masters: “Everywhere the people are in the most abject condition, exorbitantly taxed by the Sikh government, and subjected to every kind of extortion and oppression by its officers.”

The Russians, he theorised, could target Kashmiri disaffection. Wilson and Moorcroft’s general polemics about the Slavic danger took time to gain hold (Russia and Britain were allies against Napoleon), yet in 15 years theirs was the accepted opinion, as a frenzied Russophobia permeated British statecraft. This, then, was the backdrop of the First Afghan War (1838-42), as morally and tactically disastrous as any campaign in history, barely assuaged by a face-saving, punitive occupation. The British reaped only shame.

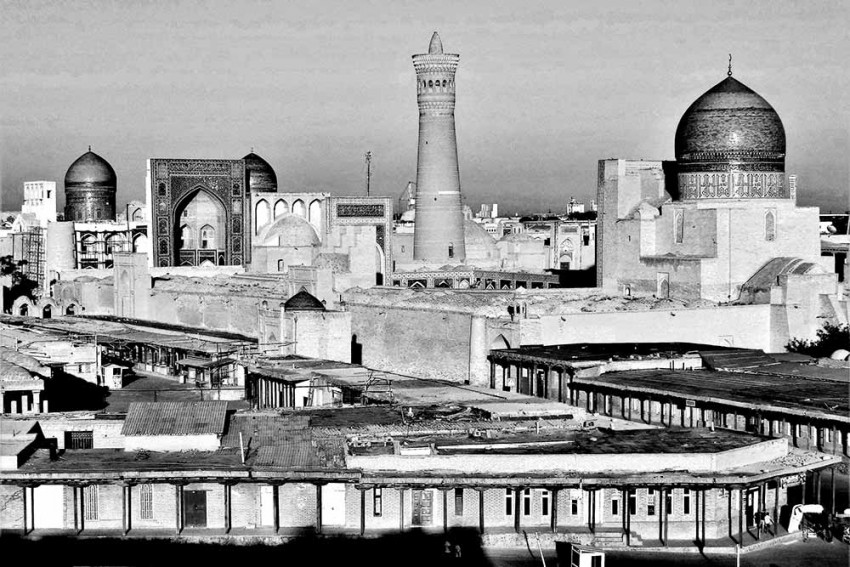

Though the sobering effect of the Crimean War (1854-56) and India’s 1857 rebellion calmed things down between Russia and Britain, it resulted in more efficient military and administrative reforms that would prime the two for another protracted bout of rivalry. In this quiet period, as Russia breathed down from Central Asia and British India hastily built up defences, they both competed for influence in Persia, Tibet and the great oasis cities straddling the ancient Silk Route of Khiva, Herat and Bokhara—in decline but still independent and militarily potent. Emissaries, spies and agents swarmed over the area—experts in topographical observation and exploration, amateur linguists and scholars who published bestselling, multi-volume accounts, precursors of the wave of great explorers of the following decades, like the Russian Mikhail Przhevalsky, the Swede Sven Hedin and the Hungarian-British Aurel Stein. All noted the cosmopolitan trading community spanning Asia, notable among them being Kashmiris with their shawls and wool.

As political power in London alternated between Gladstone and Disraeli, between a prudent ‘closed border’ policy and a rash ‘forward policy’, a fresh wave of Russian victories in the 1860s and ’70s over Tashkent, Samarkand, Bokhara and Khiva, crowned by its success in the war over Turkey in 1877, brought British fears of a dominant Russia to a fever pitch. The focus was, inevitably, Afghanistan again. Though the Second Afghan War (1878-79) was not an unmitigated disaster, it was a newer model of the same machine. The only gain: control of the Khyber Pass and some border districts. The solitary occasion when the two nations were at risk of war was when the Tsar’s forces briefly occupied Pandjeh, in eastern Afghanistan.

While pugnacity and hyperbole sufficed for the western border, the east required more stealthy means. It’s here that the Great Game got its reputation for an absorbing, even sneaky adventure, dealing thrills and dangers with an even hand. At its secret heart was the vexed question of Tibet—the more fascinatingly mysterious for centuries of being closed off by the Chinese, the suzerain power, in 1792. The Dalai Lama, its temporal and spiritual head, happily acquiesced, keen to preserve the purity of his celestial kingdom as well as his near-autonomy. Mystics salivated over the location of the mythical ‘Shambhala’, fortune-seekers over the rich lodes of gold and silver, and scholars/linguists over the richer promises of knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism.

But the British needed to pierce Tibet’s armature. The bright idea of training Indian surveyors (soon to be termed ‘pundits’) in spycraft, so they could easily, in the guise of Buddhist lamas or pilgrims, get into Tibet through Sikkim or Ladakh, occurred first to an officer of the Great Trigonometrical Survey, Thomas George Montgomerie (1830-78), who also surveyed Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh and Baltistan (an area of 7,700 sq miles) and gathered intelligence, while maintaining good relations with Gulab Singh and his successor, Ranbir Singh. A staple of the Great Game was born: the ‘pundit’, trudging through high plateaus and icy passes, keeping count of distance by a measured gait, noting, snooping, mapping, trying to establish observation posts at 20,000 feet above sea level.

Among the first to be successful was Nain Singh, who reached Lhasa in 1866 and recorded the economy, topography, military and religious festivals of Tibet. He also charted the course of the Tsangpo—which, after a wildly circuitous career among precipitous mountain gorges, enters India as the Brahmaputra. Indeed, just as Africa’s exploration for future colonial plunder was framed by the quest for the source of the Nile, so were spy missions into Tibet given depth by the search for the origins of the Tsangpo. The most famous pundit: Sarat Chandra Das (1849-1917), scholar, linguist, memoirist and intelligence agent par excellence, immortalised as Hurree Chunder Mookerjee or ‘R17’ in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim, that exemplar—and sole survivor—of Great Game fiction. His true identity as a British agent spread to Tibet from China, and an iron curtain came down over the province, by which time the pundits had explored a million square miles of unmapped territory.

The 1903-04 military ‘mission’ to Tibet, directed by viceroy Lord Curzon under Col Francis Younghusband—soldier, scholar, romantic dreamer, a stock Empire character—braved immense odds to ultimately reach Lhasa, but, in the final analysis, achieved little: senseless massacres of lightly armed Tibetans, important trade concessions, imposition of a huge indemnity, occupation of the Chumba valley and a resident in Gyantse. Much of this was done by Younghusband without approval from London, which wanted a light probe and consequently revoked much of the punitive agreement. Younghusband was shunted aside as the British resident in Srinagar. The Chinese re-assumed their nominal authority over Tibet by paying off a reduced indemnity and Curzon’s dream of Tibet being an effective buffer state between India and China remained unrealised—something that haunts Sino-Indian ties. Finally, the Anglo-Russian convention of 1907 drew the curtain on a century’s worth of trying to outdo each other on high plateaus and Central Asian deserts, amid fiercely proud peoples.

Though the Kashmir Valley was fairly immune to the high jinks of the Great Game, the frontier areas of Gilgit and Baltistan were not, and in 1893 British forces issued forth from Gilgit to relieve their compatriots besieged in a fort in Chitral, in NWFP. For the common Kashmiri, a century’s upheaval meant little, for little improved their lot. A century after Moorcroft’s observations, Albion Rajkumar Banerjee, who served as Hari Singh’s prime minister from 1927-29, resigned on moral grounds, disheartened by the utter indifference of the ruling aristocracy to the privations of the common people. “Jammu and Kashmir state…with a large Mohameddan population absolutely illiterate, with very low economic conditions…are practically governed like dumb cattle…. The administration has no or little sympathy with people’s wants and grievances.”

Like Victorian morals and prejudices, the Great Game lives on tenaciously: like Tsarist Russia’s ardent desire to make Central Asia its own, China extends itself, not just in Xinjiang or Tibet, but over those very vast spaces in a quest for developmental and civilisational lebensraum. Just as Britain harried—and parried—its adversary along Ladakh and into Tibet, India and China have been bequeathed a tussle along a border determined by the Raj’s expediency. And after two superpowers—the Soviets (1979-1989) and the US (2001-) broke their backs in Afghanistan over its internal politics, Pakistan and India worry constantly over the matter: ‘strategic depth’ is pitted against ‘strategic influence’. Then there is Kashmir; its isolation from the hurly burly broken and never really repaired since 1947, when two clashing logics of nationhood provided the first fissure. As decades pass, equal and opposite claims, counter-claims, aggression, subterfuge, terrorism, ‘freedom struggle’ and martyrhood cloud the sky over it and contribute to a bloody, sullen impasse. An imperial tussle that split open silent and rumbling perimeters has fractured into new frontiers.